Ghost towns conjure the image in the mind’s eye of abandoned towns of the Old West, with eerily swinging saloon doors, myriads of broken windows, and tumbleweeds rolling in the dust. That’s one type of ghost town, but America is liberally dotted with others, in all of the contiguous states. Some were abandoned because the railroad and later interstate highways passed them by. Some were left because the main source of employment went away. Others were abandoned because of repeated floods, or other disasters which made them untenable. Underground coal fires created abandoned towns in Pennsylvania, and since the fire still burns uncontrollably beneath the surface, will likely create others before it burns itself out.

The building of dams often creates ghost towns, many of them submerged after completion of the dam. Some have moved and reorganized themselves on higher ground or other suitable location. The real estate mantra – location, location, location – has been the justification for one site to be abandoned for another. The first English settlement in North America, Jamestown, was abandoned when the settlement at Middle Plantation, renamed Williamsburg, was declared the Virginia Colony’s capital. Many of the ghost towns in the United States are reachable with relative ease, ready to be explored by those so inclined.

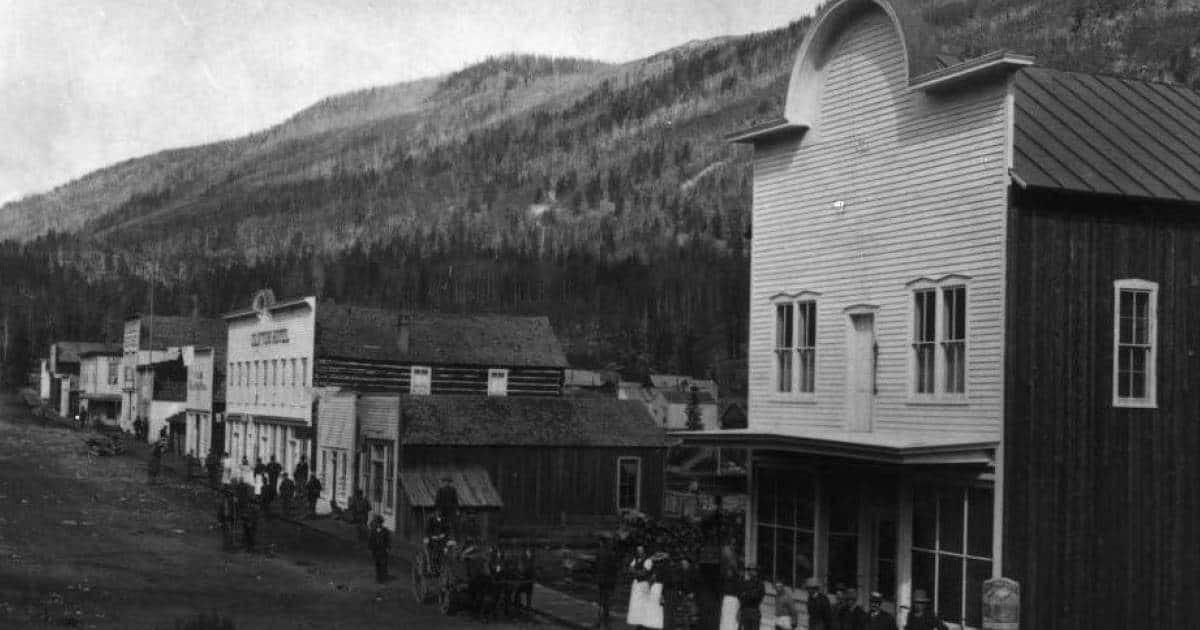

Here are ten American ghost towns which offer the curious an interesting place to visit.

Frick’s Lock, Pennsylvania

Frick’s Lock was a village which developed around two of the locks on the Schuylkill Navigation Canal, on land which was previously a farm owned by John Frick. In the early 19th century several canals were built in the young United States to move produce from interior farms to the burgeoning Eastern cities, and the manufactures from the cities to the expanding interior of the nation. Many of these canals created thriving towns along their routes.

As the nineteenth century progressed the railroads began taking more and more of the canal traffic, and many of the formerly successful towns along the waterways began to decline. Frick’s Lock was supported by rail and continued to be occupied, but its growth declined. What had until the late nineteenth century been known as Frick’s Locks, because the village had been situated between two of the locks on the canal, became Frick’s Lock, as identified by its railroad depot on the Pennsylvania Schuylkill Valley Railroad.

The disused canal was drained and filled in during the 1940s. During the 1960s construction began on the Limerick Nuclear Station on the opposite side of the Schuylkill River from Frick’s Lock. This construction led to the site’s owner, the Philadelphia Electric Company, purchasing the properties which made up the village. The buildings were abandoned and closed up. In 2000 the electric company was acquired by the Exelon Corporation.

In the 1990s a descendent of John Frick began a project to preserve the remaining buildings which had been part of Frick’s Lock, with support of the Exelon Corporation. The property was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and donated by Exelon to East Coventry Township, with eleven buildings included in the listing. These buildings were stabilized with funds provided largely by Exelon, although vandalism and ghost hunters did damage many of the structures.

Today the village, which is located off of Pennsylvania Route 724, is open for tours on a scheduled basis. The remaining structures are largely as they were when the village was abandoned, other than the ravages of time and lack of maintenance. Unescorted visits are discouraged due to the vandalism which has occurred in the past. Eventually the Schuylkill River Trail, a multiuse trail, will pass through the remains of Frick’s Lock.