It’s 4000 BCE, and the sun is slowly rising over the dark forests surrounding your village. Men and women begin to stir quietly as they prepare to go about the thousands of little tasks that it takes to survive another day. A dog barks somewhere off in the distance, disturbing the morning calm. The smell of cooking fires begins to filter through the air and into your nose. To you, all of it is pure agony. The relentless pounding inside your skull and nausea in your stomach sharpen with every noise and smell. Of course, you don’t know why your head hurts. And so you go to the one person you think might be able to help.

A few minutes later, you pull back the flap of a tent. A whirl of burning sage and strange herbs you can’t identify rushes out to meet you. Inside the tent is an old man dressed in skins and woven grasses deep in a trance as he leaves his body to speak to the spirits of your ancestors and the animals your tribe depends on for survival. In time, other people will come to refer to this type of man as a shaman or spirit healer. To you, he is simply the Wise Man, the one who knows the workings of the demons inside your skull.

He examines you closely, smudging your forehead with the soot from burnt sage. He informs you that he’s spoken with the spirits. They’ve told him what he needs to do. But there will be pain. You shrug. Pain has been a part of your life for as long as you can remember. Biting cold, broken fingers, now the pounding in your head. Maybe you’re not comfortable with it, but it’s familiar to you. Anyway, what’s to be done for it? So you grit your teeth and wait as he tells you to sit. A small blade of dark stone appears in the Wise Man’s hand.

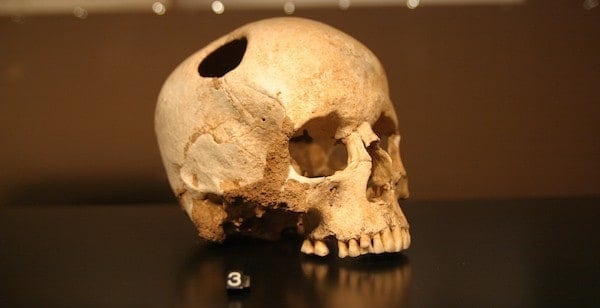

Its edge is, in the words of American novelist Cormac McCarthy, “sharper than steel… an atom thick.” It’s sharp enough to cut the flesh away from your bone, which the Wise Man begins to do. You don’t cry out, even as the blood begins to trickle down through your shaggy hair and across your neck. The pain isn’t so bad, the only thing that really unnerves you is that you can hear the stone grinding against your skull inside your head. The Wise Man makes four cuts, slicing out a small piece of your skull and folding the skin back over it.

That night, you fall into a feverish sleep as the flesh begins the process of knitting itself back together. Over the next few years, the flesh will heal and the bone will begin to grow back over the sharp edges of the cut. In time, all you’ll have left is a small soft spot near the top of your skull. You’ll live for another few years until evil gets into your bones again through a tooth. It works its way into your blood and your heart stops beating. So your bones rest beneath the earth for 6,000 years until they’re discovered by one of your descendants. She notices the hole left behind in your skull. “Why?” she asks.