Slaves resisted their bondage. Low acts of resistance were everyday occurrences such as breaking a tool, work slowdowns and stoppages, faking illness, running away for a few days, and maintaining African tribal cultures. Overt acts of resistance were revolts, hitting an overseer or master, running away to freedom, hiding, and even suicide.

Stories of resistance were passed down through the generations, influencing more slaves to resist their bondage in their own way. Slave owners failed to realize that for those people enslaved, freedom was a value worth achieving at any cost. Below are eight acts of American slave resistance.

1. Stono Rebellion 1739

Rice plantations traversed the coastal regions of South Carolina. The British colony supplied most of the food to its sugar island Barbados. Cultivating rice required a large labor force. To harvest the grain, the rice fields were flooded, and slaves stood in the water, baking. Hats provided little to no protection from the sun’s rays that literally baked the slaves to death or blinded them. Most slaves in South Carolina during the 18th century came from the Kingdom of Kongo, a Catholic region, where they were warriors, and generally worked a season or two in the Caribbean before being transported for sale in the Carolinas. Owners failed to understand that their human bondsmen were well trained in the art of warfare.

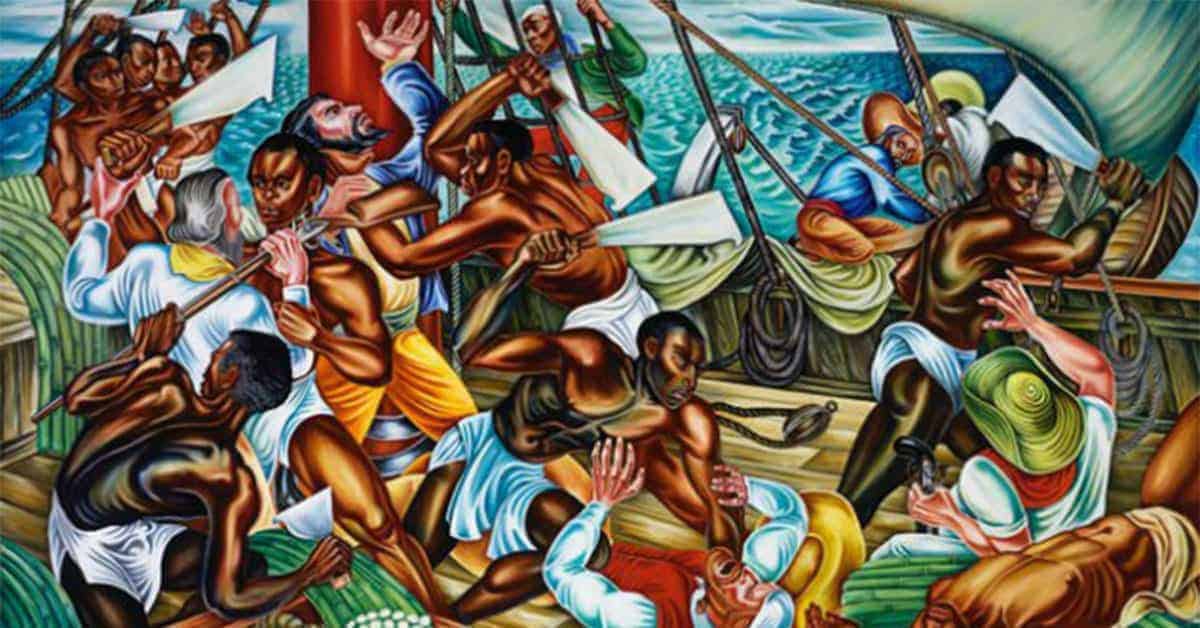

Under the leadership of a slave named Jemmy, 22 enslaved Africans gathered near the Stono River, just 20 miles southwest of Charleston, on Sunday, September 9, 1739. As families were in church celebrating the Virgin Mary’s nativity, slaves marched on the road chanting and carrying a banner that proclaimed “Liberty!” At the Stono River Bridge, slaves attacked two shopkeepers in the Hutchenson store and took guns and ammunition. As the 22 men marched toward Florida, more slaves joined their ranks. The destination for the slaves in rebellion was Spanish Florida, which as an enemy of Great Britain, was a refuge for escaped slaves.

With the group now at 81, they continued their southward march to Florida. Along the way, they burned six plantations and killed somewhere between 23 and 28 whites. As onlookers saw the rebellious slaves, they ran to warn of the impending danger. A militia of plantation owners set out to confront the mob of slaves. They intersected at the Edisto River where 23 whites and 47 slaves were killed. White colonists took the head of the dead slaves and mounted them on stakes and then placed them along the roadways as a warning to other slaves thinking about joining the revolt. Slaves that had survived the encounter were either executed or sold to sugar planters in the Caribbean.

In the aftermath of the Stono Rebellion, the colonial government in South Carolina passed the Negro Act of 1740. Slaves were not permitted to gather in groups, on a plantation there must be one white for every ten slaves, they could not learn to read or write, and the slaves were prohibited from raising their own crops, livestock, and selling any of these goods. The Act also attempted to control the brutal behavior of masters who either worked their slaves too hard or beat them excessively. This behavior was difficult to prove since only whites could bring about such charges. Plantation owners were also required to teach Christian doctrine to their slaves, something that most of them were already well versed in.