The 20th Century is full of examples of man’s inhumanity to man. The horrors of the first World War early in the century set the stage for what was to become one of the darkest periods in human history. And no event serves as a more terrible reminder of how evil people can be than the atrocities that followed in the second World War.

The crimes of Nazi Germany in occupied territories and the industrial slaughter of the Holocaust resulted in the deaths of millions of people. But the second World War was truly a global conflict and evil was found everywhere it was fought.

Though they often get less popular attention than those of the Germans, the Japanese military’s crimes were certainly horrific. The occupation of Nanking by the Japanese Army led to a maelstrom of violence that lead to tens or possibly even hundreds of thousands of deaths among the residents of the city.

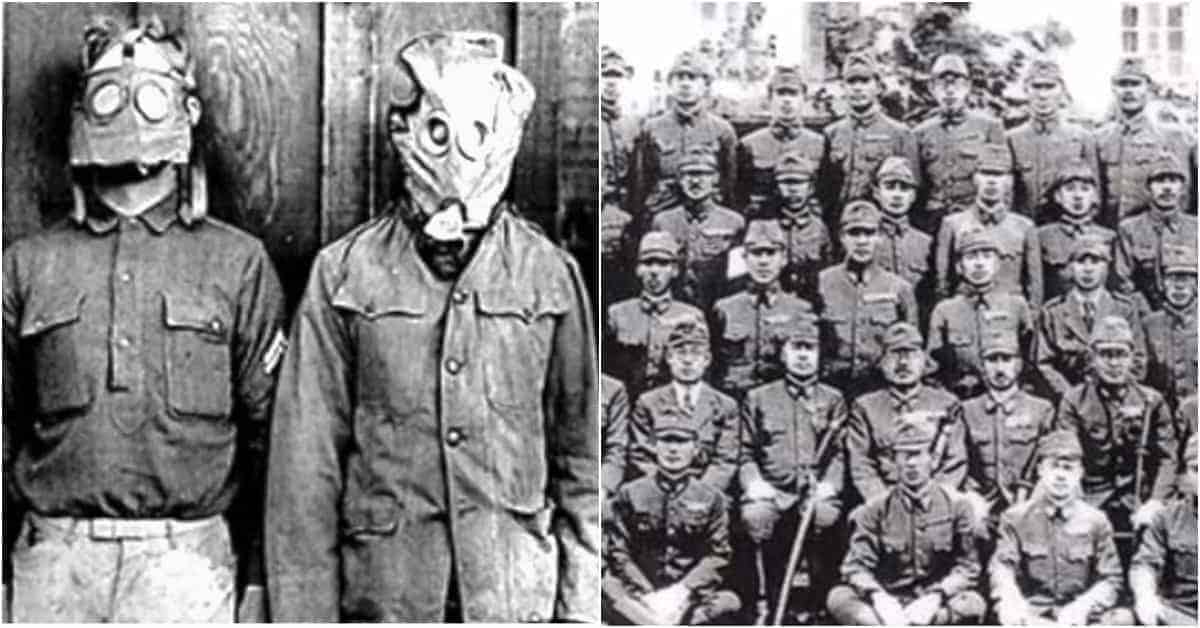

Like the Germans, the Japanese often treated the citizens in occupied territories with almost casual cruelty. Also like the Germans, the Japanese even exploited these people for horrific human experimentation. They even had a specialized unit they created to conduct these experiments: Unit 731.

The story of Unit 731 really began before the Second World War with the person who would eventually lead the unit’s activities, Shiro Ishii. Ishii was a medical officer in the Japanese military who specialized in studying infectious diseases. This kind of research was a popular subject for Japanese Army researchers like Ishii, who realized the importance of keeping troops healthy in the field. But Ishii also realized that infectious diseases could be turned against an enemy’s troops and began to advocate that the military look into developing biological weapons.

In 1930, Ishii petitioned the government for funding to form a research team that would study the effects of pandemic diseases. The government agreed and Ishii began work at the “Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory,” where he claimed publicly to be working on ways to protect Japanese troops from diseases. This was actually true in one sense. Much of Ishii’s work was dedicated to researching effective ways to treat and prevent infectious diseases. However, Ishii’s actual intentions were always far darker. He wanted to learn which diseases would be the best candidate for weaponization.

With the permission of his direct superiors in the military, Ishii began to look for ways to turn his knowledge of preventing diseases towards finding ways to spread them. Ishii began testing various diseases on animals to see which spread quickly and killed efficiently in the hopes of finding the perfect biological weapon. However, Ishii felt that what he really needed to achieve his goal were human subjects. Because his research unit operated in Tokyo, ethical concerns and fears of containing the diseases he was testing prevented him from acquiring these subjects. However, events would soon provide him with the opportunity he needed.