Silas Soule (pronounced “sole”) was one of those people for whom the passage of time has not been kind. Few today know his name nor his story, which was both remarkable and controversial. He was raised in an abolitionist New England household. His family could trace its roots in America to the Mayflower. He was an ardent abolitionist himself and a friend and associate of John Brown. He rode with the Jayhawkers in Kansas during the period when John Brown led them, and the region became known in American newspapers as Bloody Kansas. When Brown was captured after the attack on Harper’s Ferry in Virginia, Soule joined the party to mount a rescue attempt.

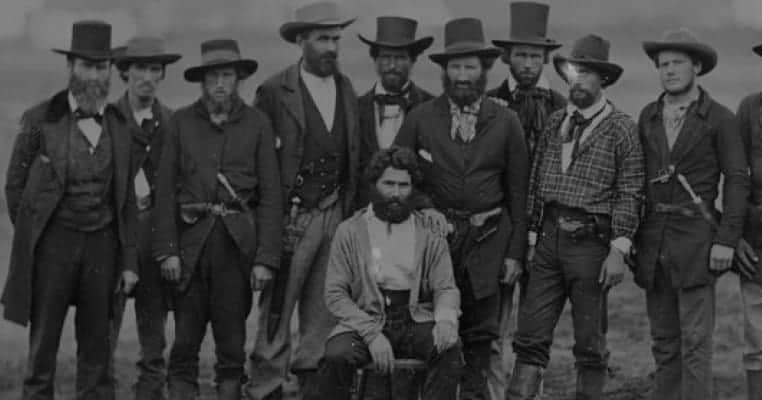

During his short life, he was often more concerned with his own conscience than the law, and on more than one occasion found himself on the wrong side of the latter. He developed skills as a jailbreaker and a bit of a con man. When the Civil War began he joined the Colorado Volunteers, serving honorably in New Mexico and Colorado, against not only Confederate troops and sympathizers, but also against Arapaho and Cheyenne under Black Kettle. He reached the rank of Captain in the army and was still serving when he was shot and killed – some say murdered – in April 1865. He faded into obscurity other than in the west, but aspects of his life deserve to be remembered. Here are some of them.

1. Silas Soule was born into an abolitionist family in 1839 Bath, Maine

The shipbuilding town of Bath, Maine was a hotbed of abolitionism in 1839, and Silas’s father, Amasa Soule, was zealous about his religion and ending the practice of slavery in America. The Emigrant Aid Society was formed in New England in 1854, expressly to help abolitionists relocate to the Kansas Territory, where they were to claim residence and vote to have the territory abolish slavery and enter the Union as a free state. Slavery supporters from Missouri and elsewhere entered the territory intent on the opposite, and Kansas descended into violence known as Bloody Kansas, with murder and the destruction of homes justified with bibles and sermons about doing the Lord’s work.

Amasa Soule answered the call in 1854 and moved his family to Lawrence, Kansas. Upon arrival, he established his home as a safe house on the Underground Railroad, a route for escaping slaves from Missouri to reach freedom in the North. Kansas was then torn between pro-slavery factions, abolitionists, slave hunters searching for runaways, and conductors on the Underground Railroad guiding the escaping slaves. At the age of fifteen, Silas became one of the latter, escorting escaping slaves and protecting them from slave hunters. To protect the conductors and slaves, New England abolitionists sent shipments to Kansas in crates marked “Bibles”. They actually were shipments of Sharps repeating rifles.