Emma Goldman wrote that “every society has the criminals it deserves.” The 1890s saw a major uprise anarchist activity. Things were especially explosive in France; Paris seemed to have a knack for producing thunderously radical political outlaws. Auguste Vaillant, Ravachol, and Emile Henry were all in their early twenties when they acted out their convictions against French society by lighting the fuses of their self-made bombs.

Background

Industrialization bred more than just mass-produced goods. A growing discontent was felt by a number of factory workers who left their rural settings for jobs that offered long hours, little pay, and substandard living conditions. The setting fueled contempt, particularly toward the bourgeoisie, whose middle-class standards were accused of being aligned with everything that was shallow and hedonistic.

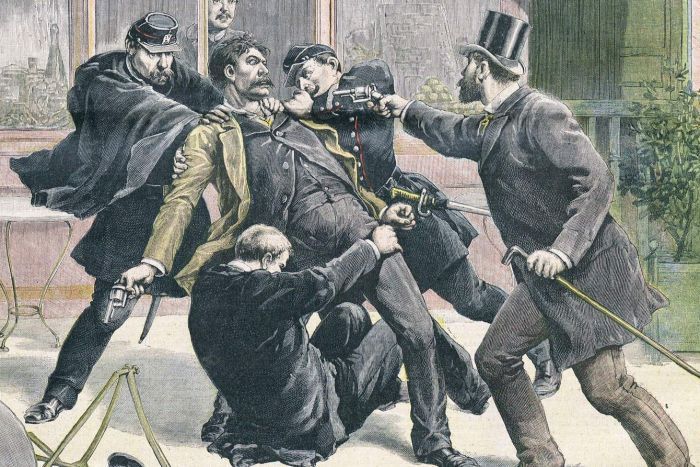

Their lack of depth was perceived to be in conjunction with an untempered appetite for material goods. They shopped while the people around them starved. Leading the charge against the bourgeoisie was Auguste Vaillant, remembered for his bombing of the French Chamber of Deputies on a cold December day in 1893. The bombing only caused slight injuries, but Vaillant was arrested, tried, and executed in February 1894.

Vaillant did not have an easy life. He was abandoned by both his parents and by the age of 12 had spent time in jail for begging and stealing food. He eventually fled to Argentina with the hope of a fresh start but struggled and finally returned to France after concluding there was no way to escape poverty’s hold on him. He settled in Paris, where he learned about anarchist ideas, which he later used as an outlet to vent his plight.

During his trial, Vaillant summarized his life had been spent bearing witness to injustices caused by capitalism. Industrialism and factories were, from his point of view, the intestines of a vampire culture sucking the life out of society. During his time in Argentina, he hoped to escape a money-driven, mass-production reality that was swallowing Europe whole. His romantic ideals were dashed. Argentina was in lockstep with the industry boom happening throughout the world, whether through factories or the raw materials needed to create the goods being made in factories, and the competitive capital spirit was thriving at the expense of the poor.

For Vaillant, returning to France only afforded him the opportunity to watch his family suffer. In the world of measuring wrong against wrong, this made more sense to him than passively standing by and watching. Vaillant underscored that his bomb was devised to harm and not kill. He saw justice in his actions, which were on par not as severe as those carried out through negligence every time a mine collapsed, or factory workers died, the proprietors of those businesses were not held accountable — this was Vaillant’s overarching reason for his actions.

His court defense was overlooked but his actions were taken seriously. The French government used his behavior to pass a wildly controversial law intended to stamp out terrorist activities which were gaining popularity. Before Vaillant, a man named François Claudius Koenigstein, better known as Ravachol, struck terror into the heart of France.