Today, we associate the Festive Season with peace and goodwill to all men. It’s a time to celebrate the turning of the year or the birth of Christ with presents, parties, and togetherness. Light and hope are its motifs, and for most children, Santa Clause – otherwise known as Father Christmas or St. Nicholas – lies at the center of the festivities.

However, there is a dark side to Christmas. A side where the elves are not Santa’s little helpers- or indeed anybody’s friends. Where in the shadows, cruel and frightful figures lurk, waiting to play tricks and do harm- especially to those who have been ‘naughty.’ Some of these figures accompany St. Nicholas on his rounds while others work alone. Some are even based in part on historical personas. All, one way or another, have one foot in a past where winter was a dangerous time, with hunger, darkness and want just waiting around the corner for the unwary or the unlucky.

Some of these figures survive today, as legends or as picturesque relics of Yuletides past, their threat dimmed by the bright lights of the modern Christmas. But they lurk in the shadows still, reminding us that, for our ancestors at least, Christmas time wasn’t always merry or bright. Here are ten of these curious – and terrifying – figures of Christmas past.

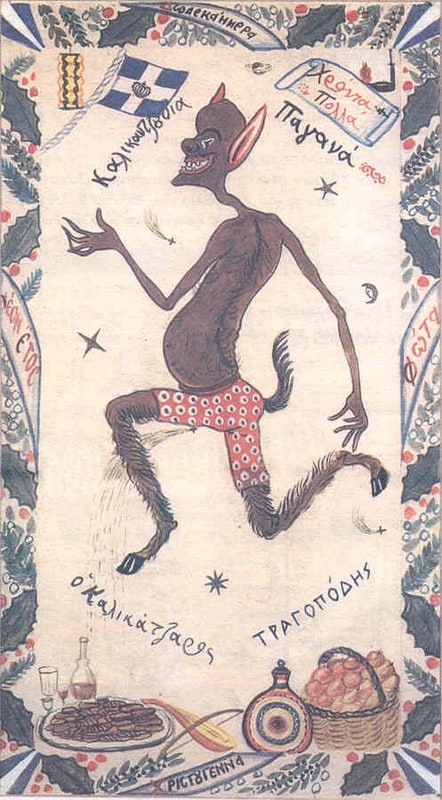

The Kallikantzaros

According to the folklore of Greece and the Balkan states, between the Winter Solstice and Epiphany, the kallikantzaros emerge. For most of the year, these light fearing goblins lived underground, working their mischief on the world tree. Every day, they relentlessly sawed at the trees’ trunk- for once the tree was down, (or so they believed), the world will fall. However, at the winter solstice, the kallikantzaros were drawn by the darkness of the year above ground. And so they took a sixteen-day holiday, causing havoc for humanity instead.

Descriptions of the Kallikantzaros vary from region to region, but all agree that they were like little black devils: small, humanlike, but with long tails and a liking for frogs and worms. The kallikantzaros were also blind- probably as a result of their subterranean existence. However, this did not impede them from making mischief.

During the day, people were safe from the Kallikantzaros because daylight is deadly to them. However, at night, the little imps were at large, waiting for victims. Anyone out alone needed to beware, for if they encountered the kallikantzaros, they would be forced to carry them about until dawn. Nor were people safe indoors, for the kallikantzaros would attempt to draw them out by imitating the voices of dead loved ones.

If their victims did not come out, the kallikantzaros would break in, sneaking through cracks in windows or the keyholes of doors-or down the chimney. Once inside, they would smash up the furniture, eat all the food, drink all the drink- and urinate on any remaining provisions. If they encountered people, the Kallikantzaros would terrify them with their hideous red eyes and hysterical laughter and with spiteful bites and scratches.

However, it was possible to thwart the Kallikantzaros. A colander placed on the doorstep could distract them from breaking in for a whole night. The kallikantzaros would attempt to count the colanders’ holes- but they could never get past two for three is a sacred number and for a kallikantzaros to speak its name was to invite certain death. If a Kallikantzaros tried the chimney instead, a burning Yule log could block their way. Burning an old shoe, or salt and incense also warded them off. Failing that, a black cross on the door would do the trick.

On the 6th January, the Kallikantzaros departed for the underworld once more. Now, the increase in light, which had been growing discretely ever since the winter solstice was finally apparent. While the people celebrated the return of the sun and the hope of spring with bonfires, the Kallikantzaros returned to sawing the world tree. Sixteen days of respite from them had allowed the tree to heal itself completely- meaning the kallikantzaros had to begin, all over again.