On September 3, 1658, Oliver Cromwell drew his last breath, bringing an end to his reign as “Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland.” It was a position that afforded him near-dictatorial power over a country that had just been through a bloody period of civil war.

Cromwell’s reign was controversial, to say the least. To some, he was a hero, but to others, he was a bloody-handed tyrant. Needless to say, Cromwell’s career in government left him with a lot of enemies. And these enemies weren’t going to let something like Cromwell’s death keep them from getting their revenge.

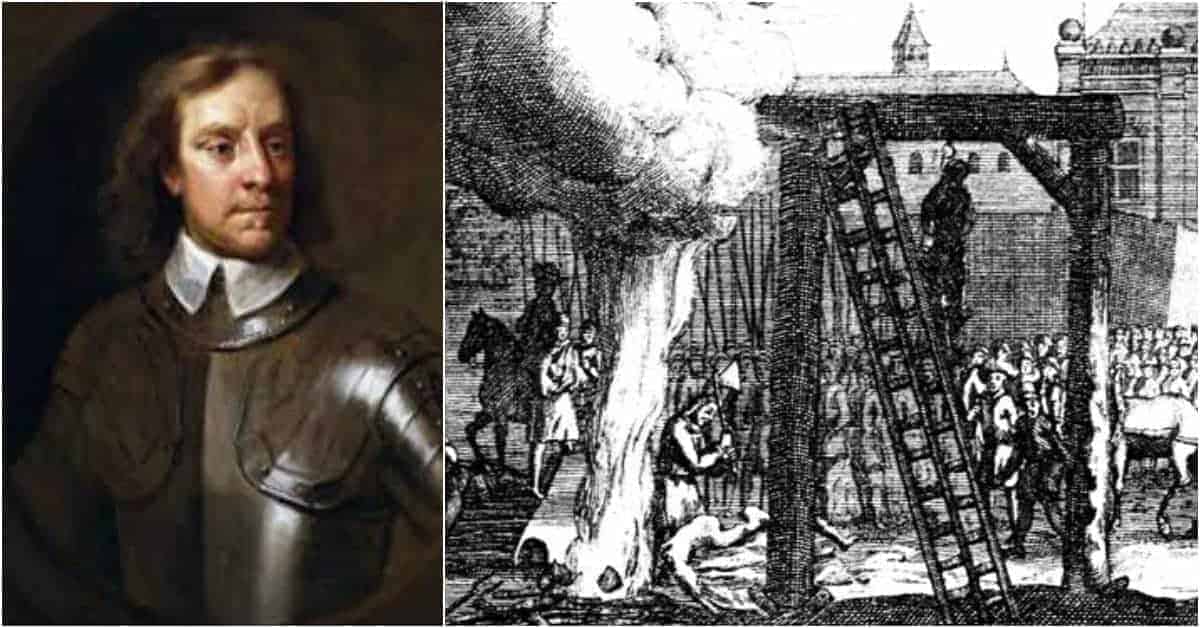

That’s why, years after his death, Oliver Cromwell’s body was pulled out of his grave to stand trial. Along with two other corpses and a dozen living men, Cromwell was charged with regicide for his role in the beheading of the previous English King. Being understandably mute in his defense, Cromwell was found guilty and sentenced to the traditional punishment for traitors to the Crown.

His body was hanged and cut into quarters. Meanwhile, his head was separated from the body and mounted on a spike, beginning a long, strange journey that would span centuries.

Of course to understand why Cromwell’s head ended up where it did, one must understand the story of the English Civil War. The origins of the Civil War really lie in the conflict between the Parliament and the reigning monarch, Charles I. At the time, Parliament lacked many of the powers that it has today. Instead, it served at the whim of Charles I, who could call and dissolve the body more or less at will. But Parliament did have one important power: the authority to raise new taxes. That power meant that the king relied on it to fund his wars.

So, while Charles might have wanted to rule more or less absolutely, the power of Parliament over the purse strings meant that he often found himself having to call the body into assembly when he needed money. Many of the members of Parliament, including Oliver Cromwell, wanted concessions of power from the King in exchange for raising new taxes. This was the basic dynamic at play for much of Charles’ reign. He would dissolve the Parliament in order to rule absolutely, angering the more democratic members of Parliament, only to call the body back into session when he ran low on cash.

But there was also another important source of tension in English society: religion. Many of the members of Parliament, again including Cromwell, were Puritans. Puritans were members of the Church of England who objected to any element of religious ritual that they considered to be “too Catholic.” This often put them at odds with Charles I, whom they considered to have Catholic sympathies. Several of Charles’ religious reforms were seen as attempts to reintroduce the Catholic Church to England and ignited protests among many of the Puritans in the English Gentry. And these conflicts between the Crown and Parliament would soon lead to war.