According to folk etymology, the term “double-cross”, as in deception by some kind of double-dealing, originated with the 18th century English master criminal Jonathan Wilde, who kept a ledger in which two crosses were literally placed next to the names of those who ran afoul of him. Wilde is also credited with giving the phrase its figurative meaning by pretending to reform and was then recruited by English magistrates to hunt down a criminal. Wilde hunted only criminals who competed against him, as he double-crossed the English authorities by using his connections to turn himself into the greatest English criminal kingpin to have ever lived, running an extensive underground empire that spanned the realm.

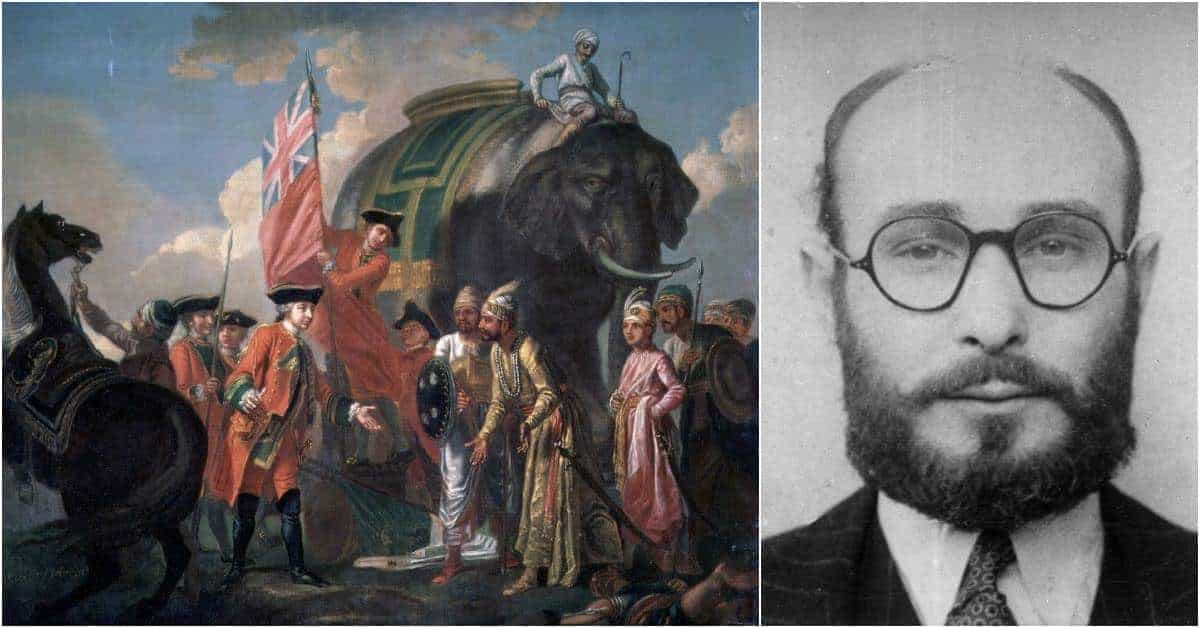

In more recent times, the term is most commonly used to refer to a trusted ally who turns against the team, such as with Hitler’s betrayal of Stalin after signing the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact in 1939, or going back a few centuries, to the Bengal army commander, Mir Jafar, who betrayed his ruler during the 1757 Battle of Plassey by sitting out the fight and keeping most of Bengal’s army out of it, letting the remainder go down to defeat against British-led forced commanded by Robert Clive.

Following are 12 of the greatest double-crosses in history.

Harold Cole and the French Resistance

Harold Cole (1906 – 1946) was an English jailbird who served during WWII in the British Army, the French Resistance – and double-crossed both by working for Germans. During his extraordinary wartime career, he lied and conned his way across France, joined the Nazis, and snitched on the Resistance, resulting in the arrest and execution of many.

By his teens, Cole was already a burglar, check forger and embezzler, and by 1939, he had served multiple stints in prison. When WWII began, he lied about his criminal history to enlist in the British Army and was sent to France. Promoted to sergeant, he was arrested for stealing money from the Sergeants’ Mess to spend on hookers and became a POW in May 1940 when the Germans captured the guardhouse where he was jailed.

He escaped and made his way to Lille, where he got in touch with the French Resistance, claiming to be a British intelligence agent sent to organize escape lines to get stranded and escaped British military personnel back home, and for some time, Cole actually did positive work, escorting escaped personnel across Nazi-occupied territory to the relative safety of Vichy France, from which they slipped into Spain and a ship back home.

However, he also embezzled from the funds intended to finance those operations to pay for a high society lifestyle of nightclubs, pricey restaurants, expensive champagne, fast cars, and faster girls. When his thefts came to light in 1941, the Resistance arrested and locked him up, but while they deliberated what to do about him, Cole escaped.

On the run from the Resistance, he turned himself into the Germans, gave them 30 pages of Resistance member names and addresses, and became an agent of the SS’ Sicherheitdienst, or SD. In the ensuing roundup, over 150 Resistance members were arrested, of whom at least 50 were executed, and Cole was present during the interrogation and torture of many of his former colleagues.

As Allied armies neared Paris in 1944, Cole fled in a Gestapo uniform. In June of 1945, he turned up in southern Germany, claiming to be a British undercover agent, and offered his services to the American occupation forces. Triple crossing, he turned against the Nazis, hunting and flushing them out of hiding, and murdering at least one of them.

The British discovered Cole whereabouts arrested him, but he escaped the prison where he was awaiting court-martial and headed to France. There, French police received a tip-off revealing his whereabouts in a central Paris apartment, and on January 8, 1946, they crept up a staircase to seize him. Their heavy tread gave them away, however, and he met them at the doorway, pistol in hand. In the ensuing shootout, the fugitive was struck multiple times and bled to death.