In the early months of 1904, Samuel Philips Verner found himself hacking his way through the thick jungles of the Congo Basin. He had already sailed a long way from his home in South Carolina and once he arrived in Africa, he hired a steamboat to take him as far up the Congo River as possible. When the boat would go no further, he hired a team of natives to guide him deep into the interior of the continent. Verner was on a mission to acquire a very rare specimen to exhibit at an upcoming exposition. And the specimen he was seeking was human.

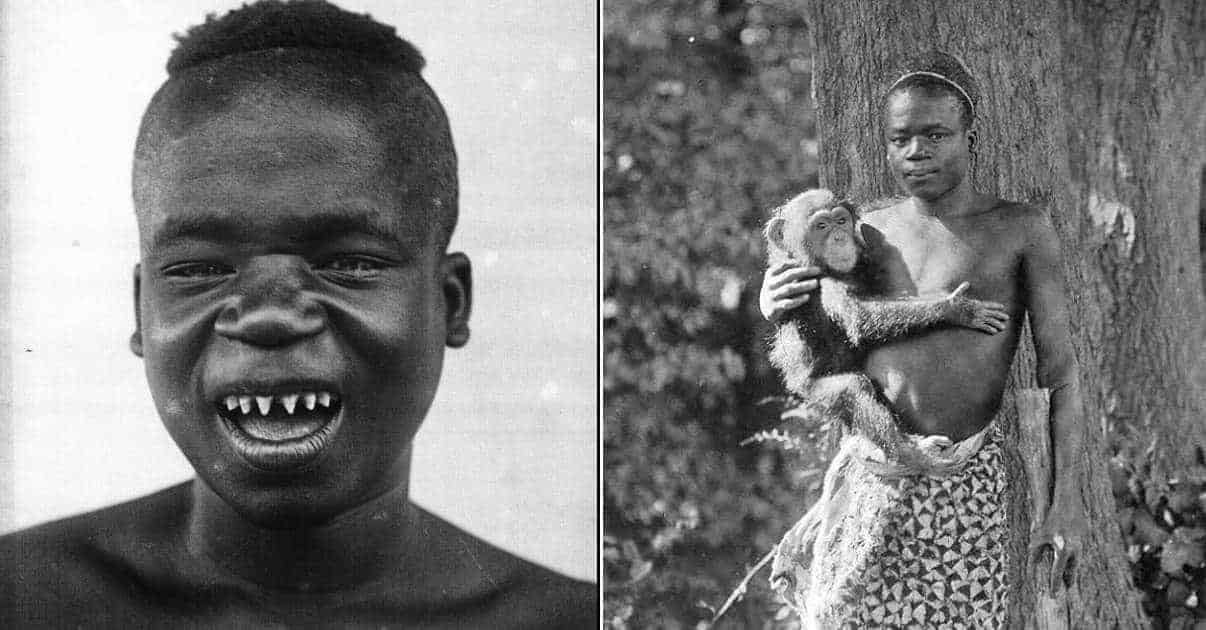

While Verner trekked through the jungle, another man, Ota Benga, was enduring his own trials. Benga was a member of the Mbuti, a tribe that lives in the forests of the Congo Basin. At the time, the Congo was the personal possession of the Belgian King. And his personal army, the Force Publique, cut a bloody swath of terror across the region. One day, while Benga was hunting, the Force Publique attacked his village, slaughtering his wife and children. With nothing to return to, Benga fled into the jungle. There, he was soon captured by slavers.

But by sheer chance, these slavers happened to cross paths with Verner a few weeks later. And when Verner saw Benga, he knew that his search was over. Benga’s tribe- the Mbuti- are pygmies, which means that they are on average less than five feet tall. And they were exactly the type of people Verner was hired to bring back to St. Louis. Verner quickly offered to buy Benga from the slavers, and they reached a deal to exchange Benga for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth. With Benga in tow, Verner set out to complete his disturbing collection.

Verner and Benga traveled to a nearby Batwa village where Verner heard he might be able to find more pygmies. But once they reached the village, they found that the Force Publique had already visited the area, and their brutality had made the people very distrustful of white men. As a result, Verner was unable to recruit any more volunteers to take part in the exhibition. But Benga spoke out, telling the Batwa that Verner had helped free him from the slavers and that he wanted to see the strange world that Verner planned to take him to.

With Benga’s help, Verner managed to convince another five pygmies to accompany him back to the United States. And Verner also recruited a number of non-pygmy Africans, including the son of a local king. The benefactor who paid for the trip made it clear that Verner was to collect as many different varieties of people as possible. In particular, he wanted people who varied in height and “stages of development.” He needed these people because he was putting together an exhibit that he thought would demonstrate the evolution of mankind. And that exhibit would take the form of a “human zoo.”