One of humanity’s less charming qualities is our tendency to fight over just about anything. European Catholics and Protestants, for example, slaughtered each other in a generational religious frenzy. Great Britain fought damn near everyone over trade, e.g. First Anglo-Dutch War, War of Jenkin’s Ear, First and Second Opium Wars, and the ideological war underpinning the Great Beatles/Rolling Stones Conflict appears doomed to perpetuity. Whether it’s trade, religion, or ideology, however, nothing gets humanity’s blood up like territory.

History is a never-ending story of land changing ownership. Occasionally, it’s a peaceful exchange where both parties walk away amicably. Greece, for example, sells island territory legitimately. Other times, two nations bloodily rip a piece of territory away from one another periodically over the course of numerous generations. Cough. Germany. Cough. France. Cough. Alsace-Lorraine. This article, however, is about neither legitimate exchange nor militant acquisition. This is a story of swindling.

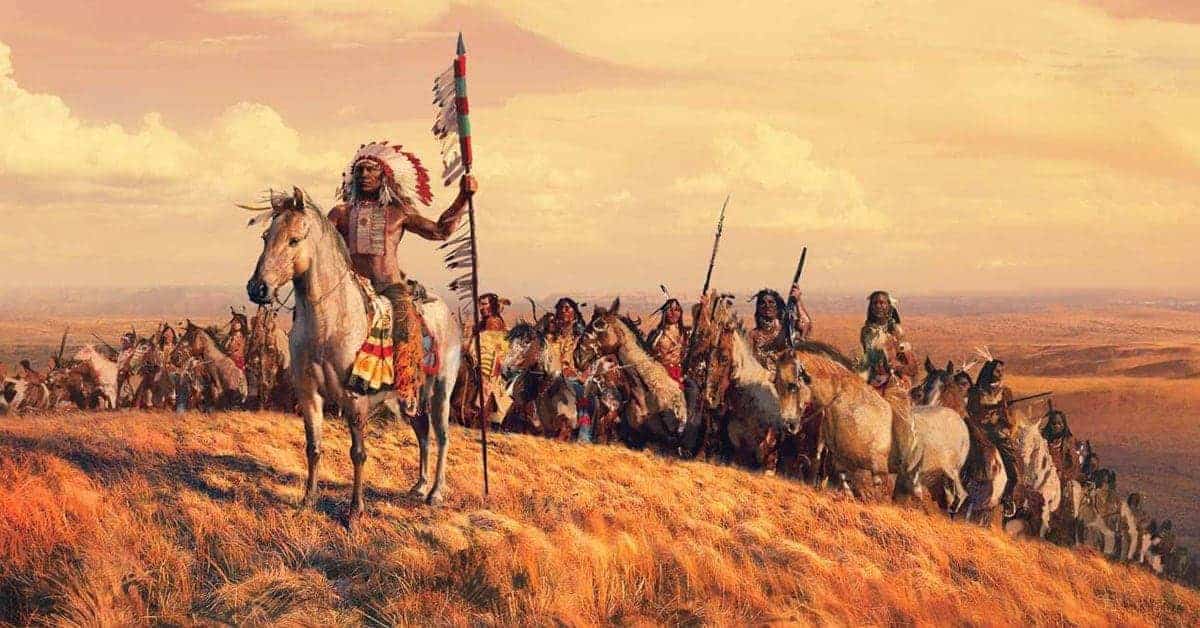

Military power played a huge role in dispossessing indigenous peoples of their territory, and those are the stories that dominate the public discourse. Sure, plenty of Americans can cite the famed, and incredibly incorrect, story regarding “Manhattan for beads,” but pop culture tends to get a little iffy on the subject when it doesn’t involve rampant militarism. Over the course of European colonization, indigenous peoples lost their land through a variety of shady approaches, and you can call it manifest destiny, lebensraum, or imperialism; just don’t call any of these methods legit.

The Walking Purchase (1737)

In 1737, Thomas and John Penn, sons of the famed Province of Pennsylvania founder William, decided the Delaware Valley would make a nice addition to their colony. The native Lenape tribe (known as Delaware Indians to the colonists) who lived there presented a bit of a problem, but the Penn’s managed to solve that issue by producing a never-before-seen bill of sale. According to the Penn boys, and their ‘rediscovered’ 1686 land agreement, the Lenape’s resided on tracts of land the tribe ceded to the Pennsylvania Colony over half a century ago.

Thomas and John presented their document to the Lenape’s with an air of “reasonableness.” They asked the natives to honor the sale’s terms, and to turn over only ‘as much land as a man can walk in a day and a half.’ The Penn boy’s father, William, had spent a lifetime learning native diplomacy and had worked to engender trust with the indigenous groups living near the colony, particularly the Lenape. William’s history of legitimate dealings with his neighbors likely played a role in the Lenape’s willingness to abide by the terms of a heretofore unknown sale. Thus, they agreed with Thomas and John’s proposal.

Thomas and John, however, possessed none of their father’s integrity. Lenape observers discovered this on the day of the “walk.” Thomas and John had quietly trained their “walkers” as distance runners and prepared clear paths for their trek. The Lenape were aghast, but a deal, as they say, is a deal.