A great deal of time in the life of a medieval monk was spent in contemplation. Within the abbey and monastery walls of Holy Orders across Medieval Christendom, brothers passed their days contemplating the Trinity, contemplating the devil, contemplating heaven and—by extension—contemplating hell. One particular monk, however, went beyond merely contemplating the devil to create an enormous illustration of him in the world’s largest (and one of the world’s strangest) medieval manuscripts: the accordingly named Devil’s Bible.

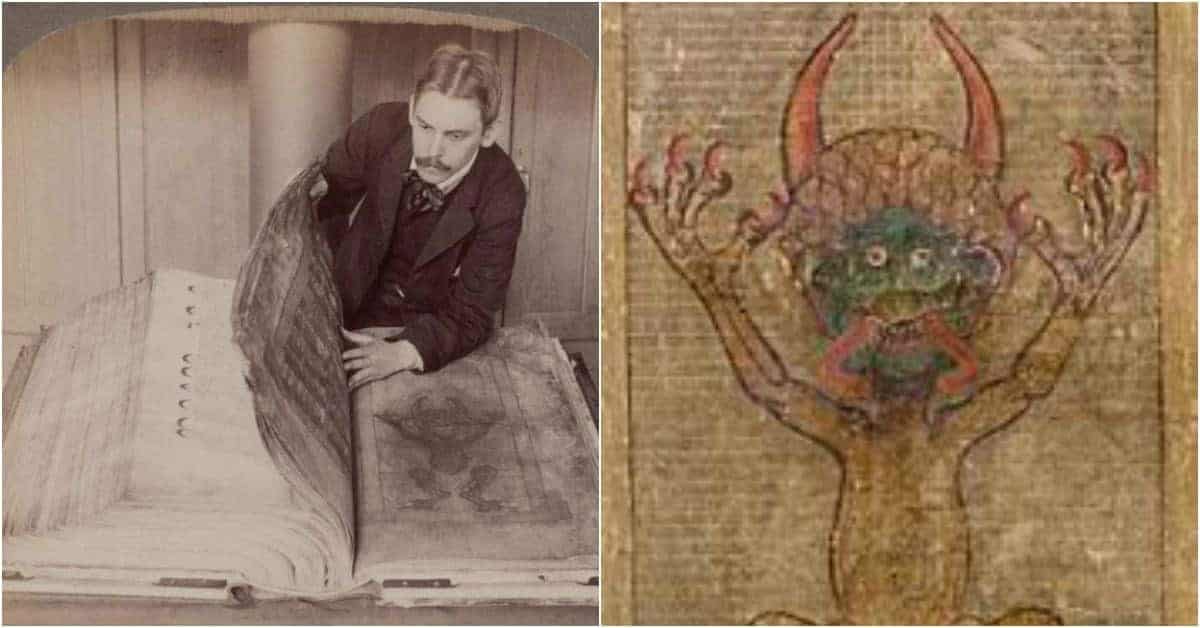

The academic name for the manuscript is the codex gigas, or “giant book” in Latin. And giant it is. Measuring a staggering 36 inches in height, 20 inches in width, and 8.7 inches thick, it contains a remarkable 310 parchment leaves or 620 pages. Such dimensions mean that the combined leather binding, metal trim, and velum of 160 donkeys that make up the manuscript weighs in at a hefty total of 165 pounds—so heavy that at least two adults are needed to carry it.

More incredible than the tome’s physical dimensions is its authorship. Owing to the consistency of the handwriting and illustrations, it’s universally agreed that the Devil’s Bible was the work of a single man. A thirteenth-century signature reading hermanus monarchus inclusus may identify the author as one “Herman the reclusive monk”. And that the author was both reclusive (and for that matter single) is perfectly evident, given the extraordinary nature of his accomplishment.

Researchers have calculated that it if someone today were to work on the manuscript 24/7, it would take them around five years to reproduce the writing alone. There’s no question that our medieval monk was incredibly committed, but no matter how much his commitment it’s safe to assume that over the years he needed some sleep. Assuming he worked full-time, therefore, it would have taken our monk at least 30 years to complete the manuscript, including all its illustrations.

The Legend of the Devil’s Bible

According to legend, the author was from Bohemia—the modern-day Czech Republic—and he began working on his manuscript early first part of the thirteenth century in a Benedictine Monastery in Podlažice, Bohemia (the modern-day Czech-Republic). History and legend make uncomfortable bedfellows here, however: while the names of famous contemporary figures more or less confirm the accuracy of the date, its place of origin is more contentious. In fact, the monastery in Podlažice was very poor, and no other surviving manuscripts have been identified that come from there.

Far more contentious than the date are the circumstances in which the Devil’s Bible was written, which are shrouded in sinister, satanic mystery. The legend of its genesis goes like this. After breaking one of his monastic vows, a Benedictine monk was sentenced to the horrendous capital punishment of being walled up alive. In a desperate, last-ditch attempt to avoid his terrible fate, the monk swore to write a manuscript in a single night that would extol the monastery and contain all human knowledge to date.