Although the Roman Empire wasn’t formed until the ascension of Octavian to the role of Emperor in 27 BC, the Republic was using its military might to expand its territories long before its dissolution. This led to a variety of conflicts, including a trio of wars against King Mithridates VI of Pontus. In these wars, Rome and Pontus fought for control of the northeastern Mediterranean.

The First Mithridatic War officially began in 89 BC. Mithridates wanted to expand his empire, but his neighbors were Roman client states. Any invasion of these territories would naturally put him in conflict with Rome. The king incorporated most of the region around the Black Sea into his kingdom and switched focus to the Kingdom of Cappadocia. He had its king murdered which placed his sister, the wife of the dead monarch, in power as regent for her son Ariarathes VII.

She married Nicomedes III of Bithynia, a traditional enemy of Pontus. Nicomedes occupied Cappadocia but Mithridates quickly forced him out and eventually killed Ariarathes. Mithridates placed his son on the throne, and Nicomedes appealed to Rome for help. After a brief power struggle and a Pontic re-occupation of Cappadocia, war was declared in 89 BC.

1 -Battle of Chaeronea (86 BC)

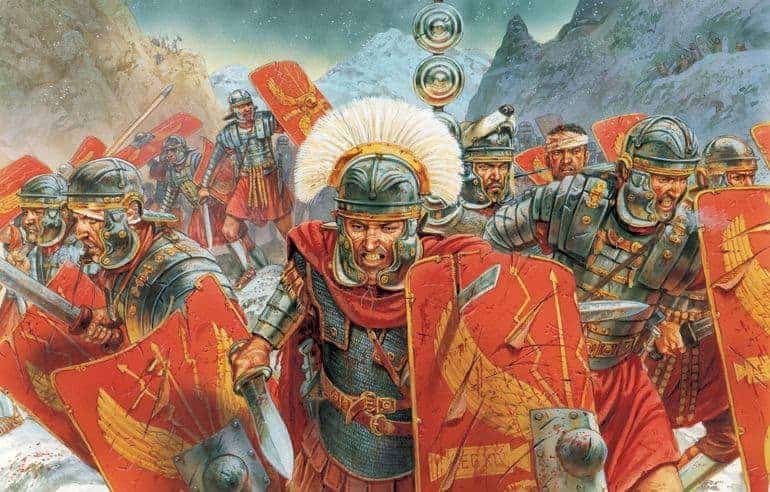

The First Mithridatic War began poorly for the Romans as Mithridates enjoyed some important victories and overran all of Asia Minor. Soon after seizing control of the province, the King of Pontus ordered a mass execution of Romans and Italians. At least 80,000 people were killed although Plutarch claims the figure was much higher. The Romans only officially declared war in 87 BC and Lucius Cornelius Sulla marched on Athens. After a lengthy siege, Sulla took the city and forced the enemy commander Archelaus into open battle at Chaeronea.

It was the same location as the famous battle in 336 BC featuring King Phillip II of Macedon and a young Alexander the Great. On this occasion, Sulla took to the field at a significant disadvantage. While estimates of the Pontus army strength vary from 76,500 to 110,000, they heavily outnumbered the 30,000 strong Roman army. Sulla’s forces contained Greek and Macedonia allied troops along with his Roman soldiers.

What Sulla lacked in numbers, he made up for in tactical discipline. He took great lengths to ensure he dictated the time and location of the battle. While the Romans had one clear commander, the Pontus forces had two. Archelaus was supposed to be the leader but had to cede control to Taxiles who arrived with a larger force. While the former wanted a war of attrition, the latter wanted to defeat the Romans decisively in open battle.

The battle was a complete disaster for the Pontic army as it was massacred by its enemy. There is no reliable data for the losses suffered by both sides. Sulla’s claim that his army lost just 12 men against 100,000 casualties for the enemy is clearly nonsense. What we do know is that the Pontic forces had to retreat and the end of the first war was just one year away.