Before the discoveries of Herculaneum and Pompeii (two cities destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD) in the 18th century, we knew relatively little about the lives of gladiators. We were reliant on ancient texts and the occasional artifact to glean knowledge of these fearsome warriors. The remains at the two locations above helped historians form a clearer picture of who the gladiators were, how they fought, and how they died.

A Brief History of Gladiatorial Combat

The first recorded gladiator games were organized by two Etruscan sons in 264 BC to commemorate the death of their father. However, the first ‘official’ games didn’t begin until 105 BC. Gladiatorial combat was a way for the aristocracy (and later, Emperors) to display their wealth, celebrate military victories and birthdays, mark visits from prominent officials, or distract the people from the various social and economic problems they faced.

Emperor Vespasian ordered the construction of the Colosseum in Rome which began in 72 AD, but he died before its completion. Titus opened the Colosseum in 80 AD with a spectacular 100-day festival of gladiator games. Construction was finally completed in around 96 AD during the reign of Domitian, and events regularly attracted crowds of up to 50,000 people. Notably, women were allowed to compete until Septimius Severus banned them in 200 AD. Honorius outlawed the games in 404 AD, some five years after closing gladiator schools. Apparently, the final straw came when a monk, who jumped between two fighters in combat, was stoned to death by the outraged crowd.

Who Were the Gladiators?

Although a large percentage of combatants were conquered peoples, slaves or criminals, a number of free men decided to fight. Those who weren’t forced into the arena did so because the rewards were potentially immense. These men usually came from a low social standing and hoped to become popular with crowds and win patronage from wealthy Romans.

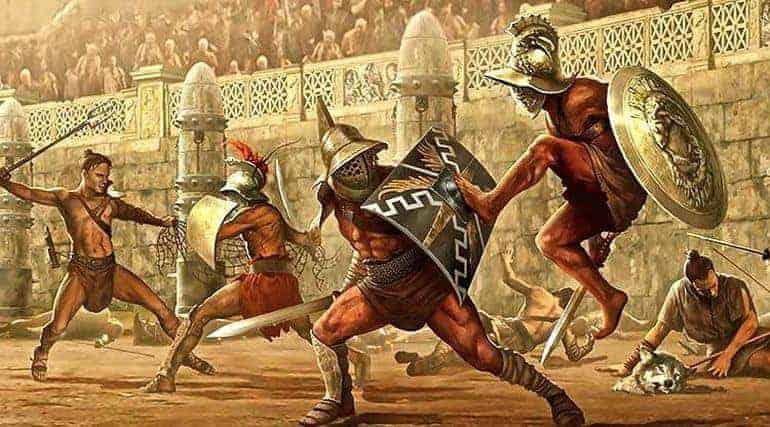

By the time the Colosseum opened, the games were well organized with warriors placed in different ‘classes’ depending on skill level, experience, and previous records. There were several types of gladiators including:

- Thraeces: Thracians who fought with a round shield and dagger.

- Equites: Entered the arena on horseback.

- Dimachaerus: Wielded two swords at once.

- Essedarii: Fought in chariots.

- Retiarius: Armed with only a net and trident.

While these individuals had to fight one another, sometimes to the death, they formed close bonds and created unions called ‘collegia’ with leaders. Whenever one of the brotherhood died in battle, the union would ensure they received a proper funeral and an inscription honoring their achievements. The family of the deceased even received financial compensation.

Life as a gladiator wasn’t easy, but the rewards were worth the risk, even for those not forced to participate. Portraits of great gladiators hung in public places, kids made clay figurines of these warriors, and the best fighters even endorsed products. Roman women loved gladiators and considered the sweat of these men to be an aphrodisiac. But how did these individuals live and die?