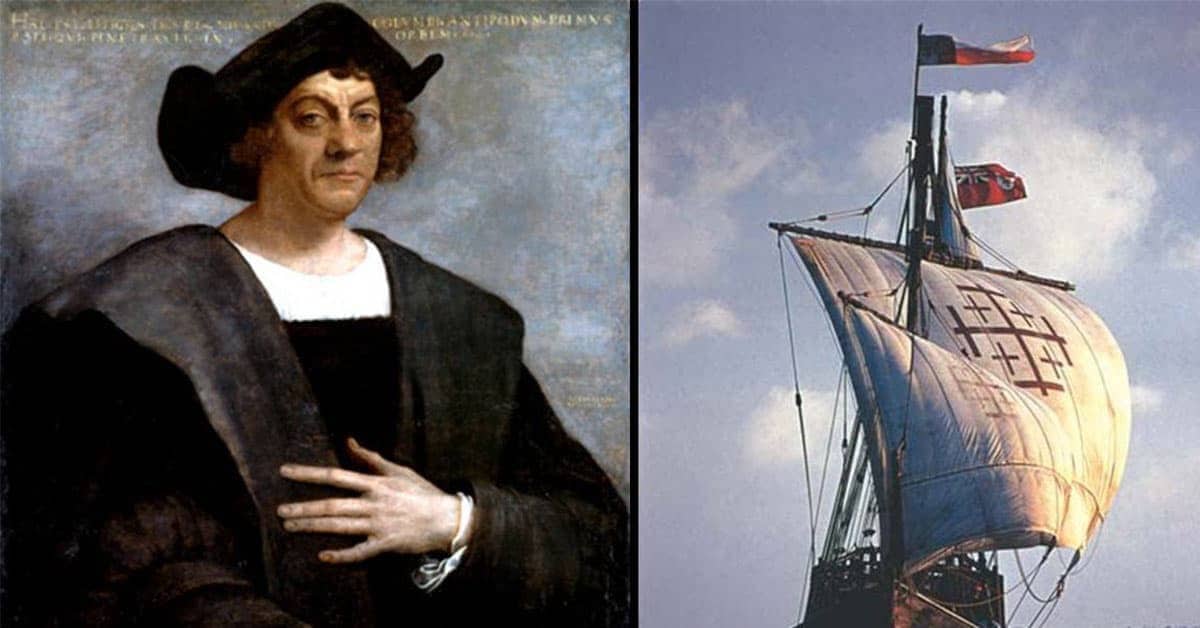

Christopher Columbus’s accomplishments are renowned throughout the world. For generations, the mnemonic “in 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue” has echoed around Anglo-American classrooms so that schoolchildren could drill to memory his “discovery” of the Americas. It’s now widely accepted, however, that Columbus wasn’t the first man—or indeed even the first European— to discover the Americas. Not only where there vast native populations already living on the continent, but it’s clear that others had sailed there before him, namely the Norse explorer Leif Erikson in the 11th century. But if trying to establish the nature of Columbus’s achievements seems a difficult task, trying to work out where he originally came from is nigh on impossible.

The scholarly status quo is that Columbus’s family came from Genoa in Liguria: a coastal region of northern Italy stretching from Tuscany in the south to Piedmont in the north. Born to a wool merchant in around 1451, the young Columbus worked on a merchant vessel and traveled extensively until 1470 when French privateers sank his ship off the coast of Portugal. Washed up on Portugal’s shores, he learned the tools of his trade in Lisbon, studying mathematics, navigation, cartography and astronomy. Eventually, in 1492, he found an audience sympathetic to his vision to make the voyage west: the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. And the rest, for want of a better phrase, is history.

The magnitude of Columbus’s expeditions to the Americas in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502 meant that before his body was even cold as it lay in state in the Spanish city of Valladolid in 1506, different countries had begun to claim him as their own. Italy, Spain and Portugal made the strongest cases. But since then France, Poland, Greece, Norway and even Scotland have also put themselves forwards as Christopher Columbus’s country of origin. And to make matters more interesting, in recent years the debate has been rekindled with new scientific and academic approaches being applied to the existing evidence.

Let’s start with the assumption that Columbus was Genovese (which, if true, makes him Liguria’s second most famous export after the region’s pesto). There’s good evidence to support this view. Firstly there’s an argument from silence: at the Spanish court in 1501, the Genoese ambassador Nicolò Oderico gave a speech lauding Columbus’s remarkable discovery. At one point he referred to Columbus as “our fellow citizen”, and as far as we know nobody contradicted him. Furthermore, two Venetian diplomats who’d been present at court would, in later writing, refer to Columbus as “the Genoese”. With Venice being no friend to Genoa at the time, it’s hard to imagine why they’d have done this if this weren’t the case.

We also have it from Columbus’s son, Ferdinand, in his father’s biography that he was Genovese. But even at this early stage, there was clearly a great deal of uncertainty shrouding Columbus’s exact origins; Ferdinand cites six potential Genoese cities: Nervi, Cogoleto, Bogliasco, Genoa, Savona and Piacenza. And then, amongst all the other fragments of evidence supporting the theory, we supposedly have a deed of primogeniture written by Columbus himself in which he explicitly states his Genovese origins:

“Siendo yo nacido en Genova… de ella salí y en ella naci”

Seeing that I was born in Genova… I come from there and was born there.