It’s been called the land of the bean and the cod, but that tribute, from a toast given at a Holy Cross Alumni banquet in 1910, was directed only to Boston. Despite Virginia getting a head start of more than a decade, Massachusetts history is replete with an impressive number of American firsts. In education the Bay colony was the first to establish a free public school, a public secondary school, and the first American university, Harvard. The first public library was in Boston and the first post office was in that city as well, operating from a tavern.

The Bay State was a leader of industry too, the first ironworks in North America being opened in Saugus, the first tannery in Lynn, and the first American lighthouse was built in Boston Harbor almost 60 years before the Revolution. Both the first canal and the first railroad to appear in America were in Massachusetts. The typewriter, the sewing machine, and the vulcanization of rubber all came from Massachusetts. The game of basketball was invented in Springfield, using peach baskets and a soccer ball. At first there were thirteen rules describing how the game is played, now the rulebook used by the NBA is more than sixty pages.

Here are ten facts about the history of Massachusetts which you may find surprising.

Shays’ Rebellion

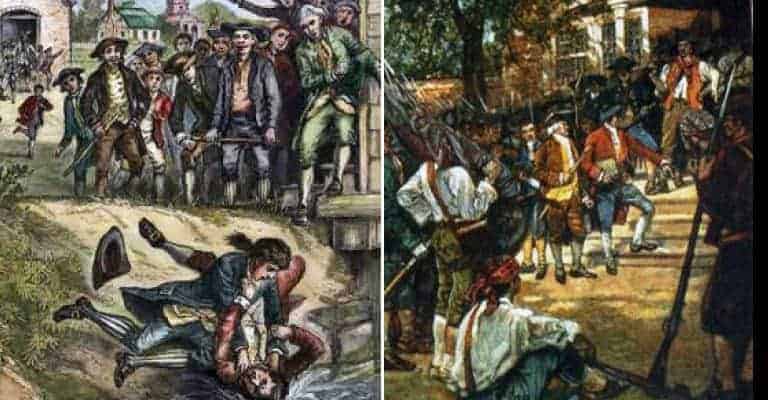

One of the post-revolutionary war events which led to the recognition of the weakness of the government under the Articles of Confederation was a 1786 armed uprising in western and central Massachusetts known as Shay’s Rebellion. It was an insurgency by mostly farmers and war veterans who had not been paid for their military service, yet were beset with near ruinous taxes. Many were members of the various town militia dotted across the state. When Congress could not raise an army to suppress the rebellion the state government was forced to create one of its own.

Like the Revolutionary War which preceded it, taxation was a root cause of the rebellion. The lack of hard currency in the state was another. When merchants passed along the demands for hard currency being imposed upon them by European traders to their local customers, many were unable to comply. The courts began to demand taxes be paid in hard currency and when the poorer farmers were unable to pay their land was confiscated. Many of these farmers were at the same time demanding of the courts payment for their war service, which they had not received for most of the war.

The rebellion began with a series of protests in central and western Massachusetts towns, where angry citizens prevented the courts from sitting and thus rendering them unable to issue tax judgments. Local authorities called on the militia to disperse the crowds. In most towns the militia refused to intervene. With no federal military the protests evolved into armed insurrection following the arrests of several of their leaders in late 1786. The rebellious farmers expressed their intent to seize the Springfield armory (which was federal property) and replace the government. Massachusetts raised a state army, and some wealthy merchants and businessmen established a private army to protect their property.

The rebels split into three separate groups in armed opposition to the state’s authority, one of which was led by Daniel Shays. When they attempted to attack the armory they were repulsed by cannon fire, leaving behind four dead, and about twenty wounded. General Benjamin Lincoln, who had received the sword of surrender by the British at Yorktown less than six years earlier, led the state troops to crush the rebellion. By early March the rebellion was quashed. Over 4,000 Massachusetts citizens acknowledged their participation in or support of the rebellion in exchange for amnesty. Eventually two men were hanged for fomenting rebellion, but Daniel Shays was not one of them.

Shays’ Rebellion brought under harsh light the inadequacies of the federal government under the Articles of Confederation. It also led to the formation of Vermont as the 14th State of the young Union. Thomas Jefferson shrugged it off by saying that a little rebellion now and then was a good thing, but his fellow Virginian George Washington began to lobby, with others, for a convention to revise the Articles, which became the Constitutional Convention. Shays remained in hiding in the Green Mountains until news reached him that he had been pardoned in 1788, when he returned to his farm and his Revolutionary War pension.