The course of human history has been defined by warfare. Indeed, ever since man first learned how to make tools has he used them to fight and kill his enemies. Only through battle have countries gained their independence, boundaries been established or rulers ascended to a position of power. In some cases, war has been a great source of evil, though sometimes war is justified and ends up being a force for good in the world. However, not all wars have been fought for noble reasons. Indeed, not all wars have been fought for even sane reasons. Sometimes logic goes out the window and men will fight their neighbors on the pettiest of pretexts.

Tragically, a king or tribal leader’s irrationality doesn’t just affect them. History is littered with examples of rulers taking offense at the smallest of things and asking the men under them to fight – and die – for their honor. At other times, the smallest of insults have outraged entire countries and caused two nations to clash. So, whether it battles fought to save face or to reclaim a seemingly worthless trinket, here are ten wars that were fought over tiny matters.

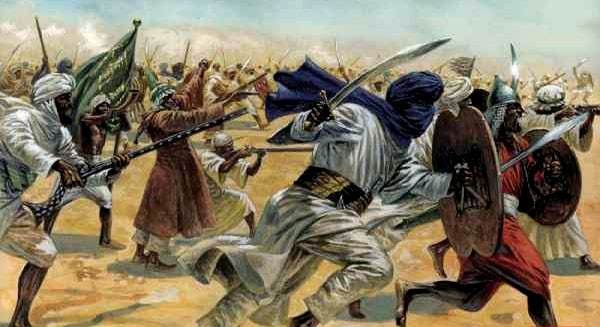

The Al-Basus War

For four long and bloody decades, two tribes battled it out in Islamic-era Arabia. Cousin fought cousin, often to the death, land was seized, and possessions looted. The cause of the conflict? A camel. What started out as a petty family dispute soon spiraled out of control and the Basus War (sometimes referred to as the Al-Basus War) came to be known as one of the most pointless, or at least the pettiest conflicts in human history.

Unlike many wars, whose origins are complex, to say the least, there’s no doubting the initial source of beef here. It all started when an elderly lady named Al-Basous, who belonged to the Bakr tribe, went to visit her niece, a young lady by the name of Jalila bint Murrah, and her brother, Jassas ibn Murrah. Now, Jalila was married to the leader of another tribe, the Taghleb people, a proud man called Kulayb. As was the custom, the three visitors arrived by camel and the old lady let her beast free to graze. So far, so civilized.

Kulayb, however, was famously protective of his territory and possessions. So, upon seeing an unknown female camel in among his own animals, he promptly retrieved his bow and arrow and killed it. Al-Basous soon learned about this and was not happy. So much so, in fact, that she summoned her nephew Jassas and demanded he fights for her honor. Sure enough, Jassas heeded his aunt’s instructions and promptly slayed the camel-killing Kulayb. This set in motion a series of tit-for-tat attacks and killings between the two rival tribes, with not even the blood ties between them enough to bring about peace.

What’s more, even outsiders couldn’t bring the conflict to a peaceful resolution. Legend has it that an ally of the Bakr tribe sent his son to see the Taghleb tribe. Here, we were supposed to sacrifice a goat and thus, in keeping with local customs of the time, bring the bloodshed to an end. However, this had the complete opposite effect. The Taghleb duly murdered the peace ambassador, bringing the third tribe into the war. The leader of these people vowed to not rest until all the Taghleb people had been wiped from the earth, and it was this thirst for revenge that finally brought an end to this pointless war. Before too long, all three sides had lost large numbers of men and grew tired of the hostilities. It might even have been the case that they forgot was they were fighting for in the first place.

Since there was no real winner, only losers, the conflict has never made it onto any list of great wars. In the Arab world, however, the Al-Basus War does, however, have the dubious honor of being shorthand for a futile and pointless fight and a moral lesson against the dangers of seeking vengeance.