Amidst the unspeakable carnage on the Western Front, it makes sense that British soldiers were desperate to squeeze in whatever carnal pleasure they could. During the bloodiest phase of the First World War, the average lifespan of a British junior officer was just six weeks, while over the course of the conflict one in ten British soldiers who signed up (or was conscripted) to serve in France and Flanders was destined never to return home. With such a primitive existential threat lurking around every corner, we shouldn’t be too surprised that the war stimulated other primitive urges in the war’s combatants.

Yet the extent to which French brothels (or maisons tolérées) were set up to service the needs of British servicemen is quite staggering. At least 137 establishments, catering for 35 towns across Northern France, were in operation by 1917. Business in these places boomed; the brothels frequented by a steady stream of clientele on rotation from the front lines to the reserve lines to postings in towns and villages a few miles behind the trenches. As one commentator remarked, apart from the distant roar of artillery fire, being stationed in one of these towns in villages you wouldn’t have known there was a war on at all.

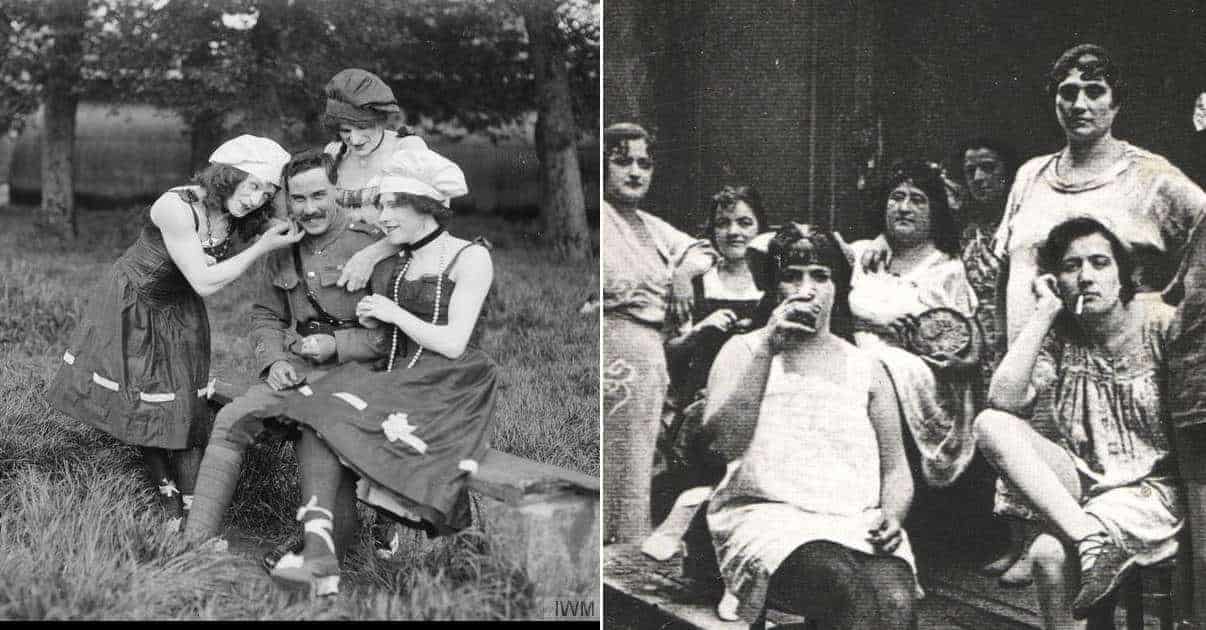

These settlements were conspicuous for their lack of young and middle-aged Frenchmen, who had been deployed to other locations across the Western Front in a desperate bid to hold back the German tide. And although the French were their allies, the British had no issues exploiting this. Anecdotes about British Tommies hitting it off with local girls abound in histories of the First World War: one anonymous veteran would even brag about how he made love to a French girl the moment he disembarked from his train—on the grass verge that substituted for a station.

If his boasts are to be believed, the same soldier was later billeted with an old Frenchman and his beautiful granddaughter. Every morning he claimed that the granddaughter would offer him coffee in bed before climbing in beside him: all to the blissful ignorance of her grandfather. Not all Tommies shared his Casanovan qualities, but for those unable to charm their way into the local culture there was always the paying alternative. And testament to how popular this alternative was is that in the space of just a year, one brothel-lined street attracted a staggering 171,000 customers.

According to eyewitness accounts, maisons tolérées were instantly recognisable, not just from their signage—a red lamp in the case of the notorious “Red Lamp” in the village of Béthune—but from the crowds of soldiers queuing up outside. The scene was described by a fresh arrival on the Western Front, Jack Wood (insert joke here about how the British Army had just got wood). Even the full Monty of trench warfare couldn’t numb him to the surprise of seeing such a long queue outside the establishment, which he likened to a scene from a football match back in Old Blighty. Albeit slightly more orderly—for is there’s one thing the British love more than anything it’s a good ol’ queue.