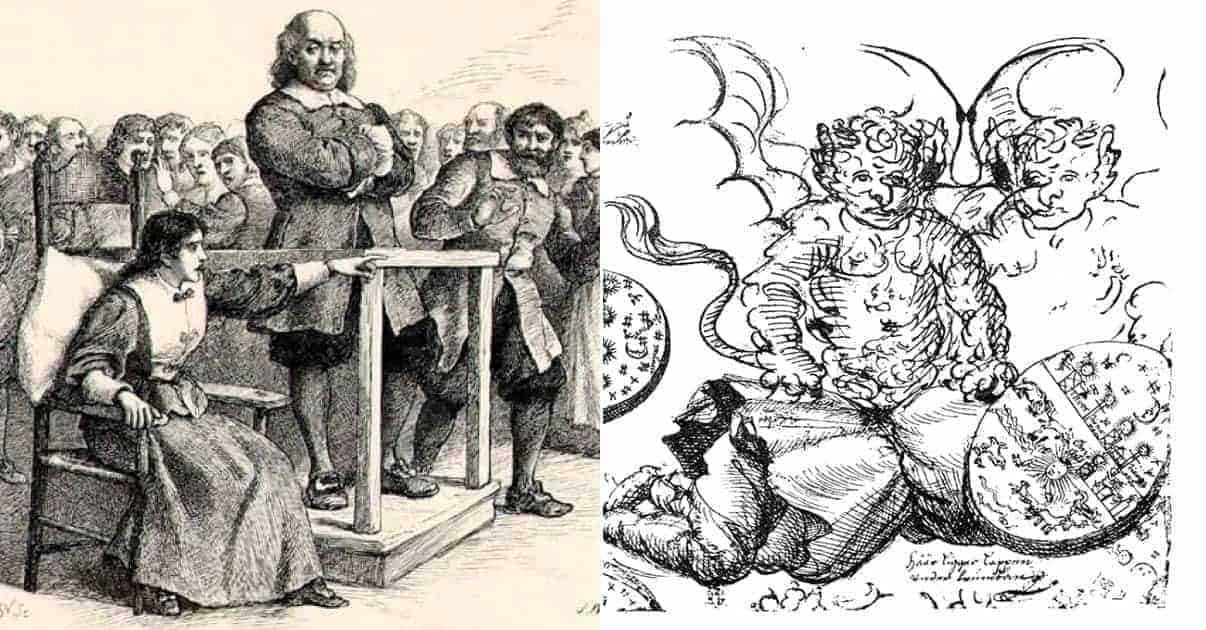

Say the word ‘witch’, and the picture that comes to mind is usually that of a woman. These women are seen as the victims of a male-dominated society, eagerly seeking scapegoats for the ills of the day amongst the old, deformed or socially marginalized.

The truth is, not all witches were old or living on the margins of society. Nor were they all women. Across Europe and its colonies between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, men, as well as women, were equally at risk from accusations, trials, and executions for witchcraft.

Some of these men did indeed live on the margins of society, falling prey to society’s fear of the ‘other’ and beliefs outside of their cultural sphere. Others were ill or deluded. Some were innocent bystanders caught up in the religious or political wrangling of their day. Others were the victims of greed, malice or vengeance.

A small minority, like some of their female counterparts, honestly did believe they had magical powers. Even if used innocently, these perceived abilities were enough to damn them to the rope or the fire. For by the height of the witch craze, the use of magic of any sort was the mark of the devil’s disciples. Few escaped such a charge. Here are just twelve men tried for witchcraft in the medieval or early modern period.

Quiwe Baarsenl

The Sami or Laplanders are the indigenous people of Arctic Scandinavia. They are best known as reindeer herders. However, from early times they were also revered and feared for the powers of their shamans, the Noaidi. Old Norse society tried to ban its people from consulting the Sami. However, people still did and continued to do so well into the Christian era.

Quiwe Baarseni was a Noaidi trained Sami, working as a servant in the town of Aaroya in the Finnemark territory of the extreme northeast of Norway. The settlement lay along the Altafjord where fishing was a significant business. So people desiring fair weather at sea often consulted Quiwe. It was this activity that led to him being one of twenty-six Sami accused of witchcraft in the seventeenth century.

On November 1, 1625, Niels Jonsen, a local fisherman from nearby Rognsund, wanted to summon a fair wind for a fishing voyage to the village of Hasvag. So he consulted Quiwe. Quiwe agreed to help him. At his trial, he explained that he took off his shoe and washed his bare right foot in the calm sea waters saying: “wind to land, wind to land.” Satisfied, the Niels Jonsen set off.

Not long afterward, the wife of Oluf Oresen, one of the crew, visited Quiwe. For a keg of beer, she asked the shaman to raise a favorable homeward wind for the fishing boat. This time, Quirwe threw a piglet into the sea, calling “wind to land, wind to land.” However, the piglet squirmed too much, and the noaidi warned his customer that this could have made the wind too strong. “God have mercy on them,” he told her, “I am afraid that they have left prematurely and that the wind will be too strong.”

A storm arose, and Jonsen, Oluf Oresen, and three others crewmen drowned. Two years later on May 9, 1627, Quiwe Baarsenl appeared in Hasvag court charged with causing drowning by witchcraft. Quiwe did not deny his abilities. He explained he had called the winds by shamanism but said that was the limit of his craft. He had, for instance, never cast ‘runic spells” using shamanic drums which called upon totem animals and spirits.

This explanation cut no ice with the court. The court classed Quiwe’s knowledge of spirits as consorting with demons. The fact that five people had drowned after a spell he cast was enough to convict him. The authorities burnt him soon afterwards.