It doesn’t take much for copyright disputes to turn nasty. Intellectual property, being so personal by nature, is one of the most contentious things you can steal, especially when it has considerable financial potential. It’s precisely for this reason that the last few centuries have seen an enormous body of legislation passed to protect the rights of the original owner.

Traditionally, we’re taught that the first copyright law was the British “Statute of Anne” passed in 1710. Legally speaking, this is true. But the statute doesn’t represent the first historical example of a copyright dispute and arbitration. That honor belongs, surprisingly, to the Dark Ages, which has shed light on one illuminating, and notably bloody, story.

The dispute in question took place in sixth-century Ireland and involved two saints who disagreed over one’s right to copy a manuscript belonging to the other. It might sound trivial. But despite the participants being literal saints, the dispute may not only be the oldest copyright battle in recorded history but also the bloodiest. For if we take the legend at its word, the dispute soon escalated into a pitched battle that resulted in the loss of some 3,000 lives.

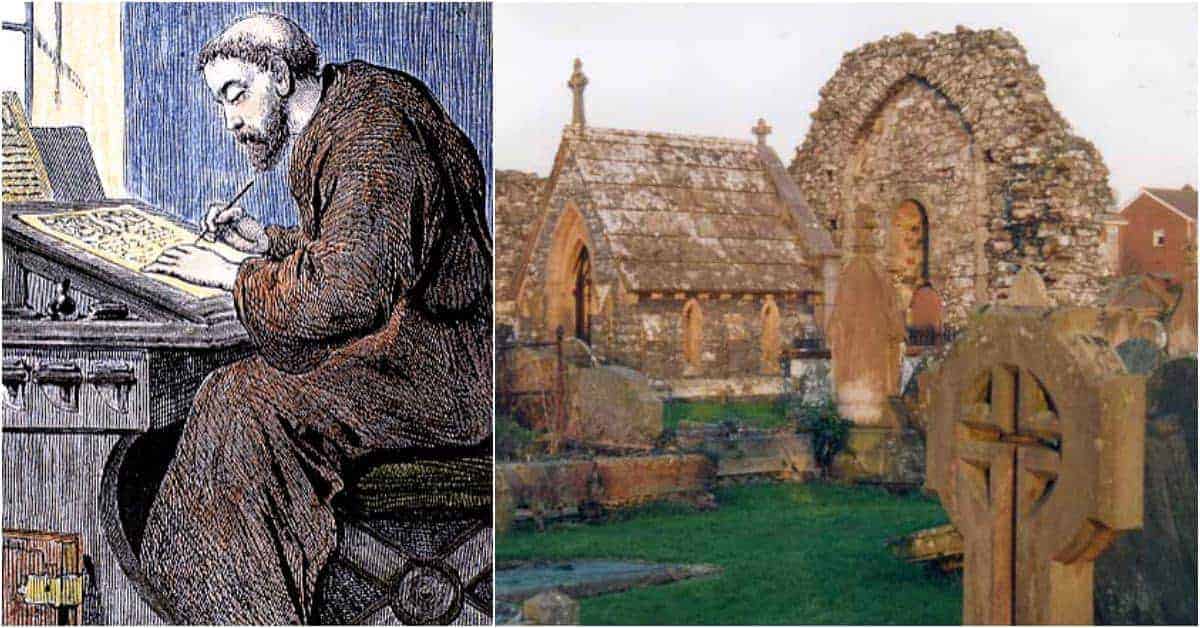

The two men involved were monks at Movilla Abbey in County Down, Northern Ireland. One was St. Finian (495 – 589), the founder of the abbey (540) and a nationally revered teacher of translation and transcription. The other was St. Columba (521 – 597), Finian’s best student, and later one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland.

The prized text was a copy of the Bible belonging to St Finian. This copy was especially valuable because it embodied the first Vulgate Latin translation from Hebrew, painstakingly undertaken two hundred years earlier by the fourth-century historian, theologian, and translator, Saint Jerome. Finian brought this copy of Jerome’s translation back with him from Rome, and the presence of this remarkable manuscript—the only Latin one in Ireland—brought considerable prestige to his abbey as a great centre of learning.

Finian’s idea was to translate and transcribe the text from Latin to Gaelic before disseminating it throughout abbeys and monasteries across Ireland. What he didn’t know was that his star student, Columba, had also had the same idea. Columba was one of Movilla Abbey’s most famous alumni. As deacon he performed a miracle, re-enacting Jesus’s popular party-trick of turning water into wine to the great delight of his fraternity. He took a brief leave of absence during the 540s. But he returned in 550 to visit his old teacher, who had recently returned from Rome with his prized manuscript.

After the text’s arrival in the monastery, Columba secretly began stealing it from Finian and working on producing his own translation. Known as either the “Cathach of St. Columba” or the “Psalter of St. Columba” the text still survives today, providing us with both the earliest Gaelic translation of the Psalter and the earliest example of Irish writing. Whether or not it was indeed copied by Columba, however, remains a contentious issue among historians.