Con artists not only have the ability to sell a lie with a straight face, they know how to select the most gullible elements of society carefully. It doesn’t matter if you are a doctor, professor or rocket scientist, if you possess certain characteristics, you could become the victim of a financial scam.

According to research conducted by Boston University, victims of financial swindles have specific traits. They are usually very trusting (gullible), have a high tolerance for risk, and feel the need to be part of a special group. The best con artists can read people like a book and quickly separate the cautious from the reckless.

In this article, I look at 5 incredible scams that almost defy belief in their audacity. In the interests of clarity, #5 is not a con (as it wasn’t illegal and didn’t involve stealing from anyone), but it warrants a place on the list for its cleverness and the fact that a corporation suffered!

1 – Victor Lustig Sold the Eiffel Tower – Twice!

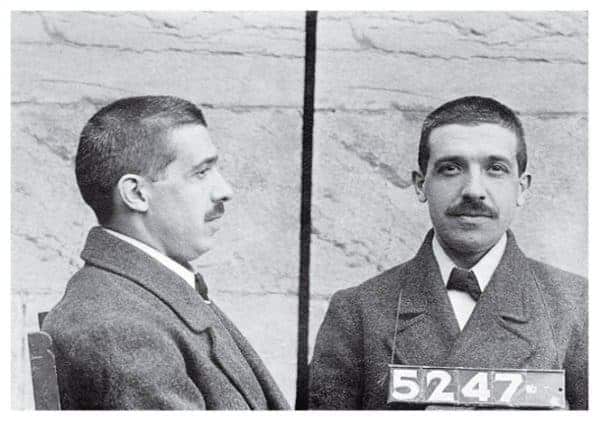

When it comes to history’s greatest scams, it is difficult to match the feat of Victor Lustig, who somehow managed to trick two different sets of investors into ‘buying’ the Eiffel Tower. While his ‘marks’ were clearly morons, you have to admire Lustig’s audacity and credit him for having incredible powers of persuasion.

Lustig was born in modern day Czech Republic in 1890 and quickly displayed an aptitude for conning people. He was a charming, highly intelligent individual who was fluent in several languages. Lustig loved gambling, so he eagerly embarked on cruise ship voyages across the Atlantic because he found a number of wealthy people who were easy to scam. World War I put an end to his cruise ship exploits but he found plenty of suckers when he moved to the United States during the Roaring Twenties.

Lustig perpetrated a host of successful scams throughout his career including the Rumanian Money Box. He would tell clients that he had a machine capable of copying $100 bills, but it took six hours to print one out. Greedy wealthy investors were only too happy to take it off his hands for sums of up to $30,000. The box would ‘print’ two bills in 12 hours but only produced blank paper after that. By then, the client had purchased the machine and Lustig was long gone.

His most audacious capers were undoubtedly the Eiffel Tower episodes. In May 1925, he traveled to Paris with his sidekick ‘Dapper’ Dan Collins. After reading a newspaper article about how the Eiffel Tower needed to be repaired but the government was considering tearing it down because the repair was so costly, Lustig decided he would ‘sell’ the rights to knock down the landmark.

He got an expert counterfeiter to create official government stationery that said Lustig was acting in an official capacity and had the power to negotiate a contract. He sent letters to five wealthy scrap iron dealers and arranged to meet them in his hotel. Lustig offered some bluster about how the Tower was never supposed to be a permanent structure, and within days, all five men submitted bids. Lustig wanted the easiest ‘mark’ rather than the highest bidder, so he settled on Andre Poisson as the target.

Lustig effectively asked Poisson for a bribe to complete the ‘sale’ and Poisson happily obliged. Lustig left Paris for Austria and spent his mark’s money gleefully. He read Parisian newspapers every day for news of the con, but nothing was ever written. Lustig concluded that Poisson was too embarrassed to report the scam to the police.

It would have been wise for Lustig to accept his ill-gotten gains happily but the conman couldn’t resist pulling the same trick with five different scrap iron dealers just one month later! On this occasion, the victim of the scam contacted the police so Lustig and Collins fled before they could be arrested. He was eventually nailed on charges of producing counterfeit banknotes in 1935, and while he escaped prison, Lustig was recaptured and sent to the infamous Alcatraz prison where he died in 1947.