In the early months of the Civil War, soldiers of both sides who were unfortunate enough to be taken prisoner could look forward to a short captivity. Both armies, officered by men who had largely shared training and military tradition, practiced the 18th-century procedures of parole and exchange.

Prisoners were exchanged between the armies on a rank for rank basis – private for private, sergeant for sergeant, fifteen privates for one colonel, and so on – while officers were freely granted the freedom of the enemy camp (within limits) in exchange for their parole – a promise that they would not try to escape or act against the enemy until they were properly exchanged. It was not unusual of an evening to see captured Union officers playing cards or sharing whiskey with their Confederate counterparts.

This civility – the dying gasps of chivalrous behavior – did not last once Northern generals grasped the hard facts of the situation between North and South. Compared to the South, the North had vast resources of manpower, while lost Johnny Rebs could not be replaced. It cost the enemy food, clothing, shelter, and manpower to restrain prisoners, something the North could afford and the South could not.

Prisoner exchanges helped the South by returning trained veteran soldiers to their ranks. By the same logic, forcing the South to care for Union prisoners in their custody drained resources and manpower.

When the South began to treat captured Union black soldiers – they were referred to as Colored Troops in the parlance of the time – as escaped slaves rather than prisoners of war, the North finally broke existing agreements regarding prisoners and the development of prisoner of war camps for extended custody began in the warring states. In the North camps opened in Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, and elsewhere, often on the sites of former training camps for the steadily growing Union armies. Captured Confederate troops often found better rations and living conditions than they had experienced within the ranks of the dwindling Southern armies, at least until arriving at the prison camps.

In the South, Union troops held in Southern camps found somewhat different conditions. Many of the Southern camps were built near water which in the extended months of the Southern summer became mosquito-infested swamps, with attendant malaria spreading among the prisoners. Cholera and typhus were also rampant in some camps. The South had little food for its troops and less for its prisoners, a situation that worsened steadily as the war went on.

As has been the case in all wars throughout history, some officers and men chosen to serve as jailers over their vanquished enemies became tyrants without conscience, doing all they could to heighten the misery of their charges. Southern prisons became notorious for the suffering of the men held within, their names synonymous with misery. One such was Richmond’s Libby Prison. Another was Camp Sumter, known to history as Andersonville.

Camp Sumter

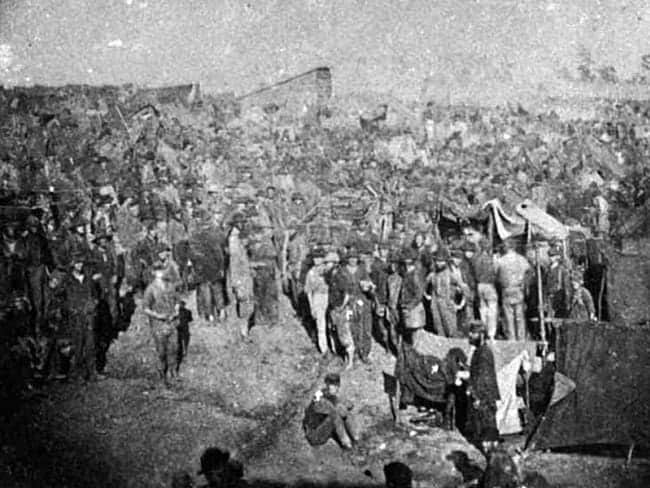

Camp Sumter (known in the North as Andersonville Prison) was opened in south central Georgia during the winter of 1864, and during its just over one year of operation held up to 45,000 Union prisoners. Of these, almost 13,000 died. Some deaths were from complications of battlefield wounds poorly treated, but most were from malnutrition leading to scurvy, dysentery, typhus, and other deadly diseases which today are easily controlled through proper diet and hygiene. The prisoners subsided largely on parched corn, chicory weed, and rarely, dried salted fish.

The main source of freshwater was Stockade Creek, which ran through the camp inside the fence line, and was unfortunately used by many men as both a washing place and a sewer, ensuring that the water further downstream but still within the camp was polluted. Warmth was provided by open firepits and a few scattered stoves, and while the camp was surrounded by forest little wood was provided to the prisoners, nor were they permitted to forage.

During wet months or following heavy summer rains, Stockade Creek turned a large portion of the enclosed grounds into bogs and swamp, infested with the impressively aggressive mosquitos and blackflies of the Deep South. Despite these and the diseases they carried, the majority of the deaths in the camp were from other causes, chiefly scorbutic dysentery (known as the bloody flux) a severe form of diarrhea caused by a shortage of vitamin C.

The majority of prisoners lived in thrown together hovels covered with scraps of blankets or rags, or else in the open air, as the construction of the planned wooden huts to house the prisoners were never completed.