The fabled feud between the Hatfields of West Virginia and the McCoys of Kentucky was one of the most storied of American history. It began in 1863, the same year West Virginia was admitted to the Union as a state, separated from the Virginia which had become the most critical state of the Confederacy. Both families for the most part supported the Confederacy during the Civil War and participated in the border warfare which erupted among the population. But one member of the McCoy clan openly supported the Union, enlisting in the 45th Kentucky regiment in 1863. The feud erupted into open violence during the war, in part covered by quasi-legal actions as a result of the conflict.

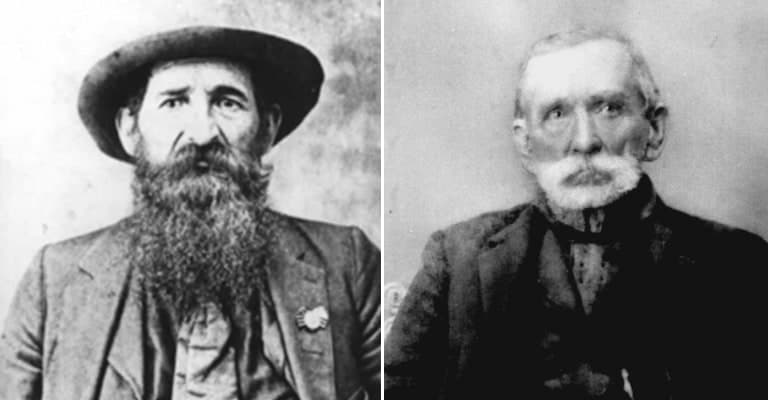

It had its roots in issues which preceded the American Civil War and carried over well beyond the end of hostilities in 1865. Both families participated in the manufacture and sale of illegal whisky in the mountainous country around Tug Fork on the Big Sandy River. Both maintained contacts with the legal authorities on their sides of the river, the Hatfields in Logan County (in a region which is now Mingo County) in West Virginia, the McCoys in Pike County, Kentucky. The Hatfields were relatively well-to-do for the region and the time, earning their money from timber and whiskey, and considering the McCoys to be little more than white trash, thieves, and murderers. Here is the story of the feud which entered the American language as the symbol of longstanding hatred and violence between families.

1. The feud began in earnest during the American Civil War

In the early days of the Civil War, the western counties of Virginia seceded from the state which had seceded from the Union, creating the new state of West Virginia. The state’s residents were divided in their loyalties with some supporting the Confederacy and others supporting the Union. The same situation existed in Kentucky, particularly in the region of the state which was part of Appalachia. Both the Hatfield family, an extended clan in the Big Sandy River region of West Virginia, and the McCoy clan of Kentucky, for the most part, supported the South, and men from both families served in the irregular forces of the regions as well as in the Confederate regiments raised in Kentucky and Virginia. Many of the units were home guard militia regiments.

As the Civil War evolved, irregular units and militia regiments frequently ambushed and killed those of the opposing view. The Pike County Home Guards were one such unit which supported the Union, with a company of the guards led by William Francis, a close friend of the McCoy family. His guards shot Moses Cline in an ambush, and though Cline survived, his friend William Anderson Hatfield – known as “Devil Anse” or simply “Anse” – retaliated in 1863 by ambushing Francis as he left his home, killing him. The bad blood between the McCoys and the Hatfields began to take on a personal nature as well as political during the sporadic raiding in 1863, while Asa Harmon McCoy recovered from wounds he received in battle in a hospital in Maryland. Harmon had been serving with the 45th Kentucky Infantry regiment of the Union Army.