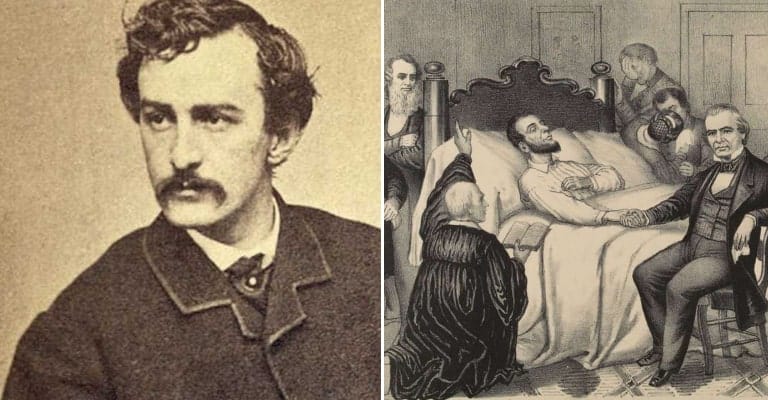

John Wilkes Booth was nearly as well known as the man he had just shot President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865. In one of history’s most melodramatic moments, he leaped from the President’s box to the stage, brandishing a bloodied bowie knife, and exited stage right. Some reported he shouted, “Sic Semper Tyrannis” (thus always to tyrants, the motto of Virginia, as well as Brutus’s words to Caesar as he stabbed him) as he made his hasty exit. Whether he did or not, it was his last performance before an audience. For what remained of his life he would be on the run, the most wanted man in America. He expected reception as a hero in the South, having killed its worst enemy. Instead, he was run to ground mercilessly by a nation bent on achieving justice.

There was at the time no Federal police force such as the FBI. The Secret Service had yet to be created, the slain President had only hours earlier signed the bill which would allow it to be formed. There was no law making the murder of the President a federal crime, his killing was under the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia’s thoroughly inept police force. The United States was on unfamiliar ground, legally speaking. The President had been murdered. His murderer was nationally famous. Where had he fled? Who had helped him escape? Was the action a plot engendered by the collapsing government of the Confederacy? Here is the story of the hunt for John Wilkes Booth and his co-conspirators in 1865.

1. Booth made no attempt to disguise himself when he killed the President

It began amidst a roar of laughter incited by a line uttered by the only actor on the stage of Ford’s theatre at the time, Harry Hawks. There was the bang of a gunshot, the smell of gunpowder, and a piercing scream from the President’s box. Suddenly another actor leaped to the stage, waving a large knife. Members of the audience were startled to recognize him as John Wilkes Booth, arguably the most famous actor in America at the time, one of a family of notable actors. Booth moved rapidly across the stage, past the startled Hawks, and vanished from sight. The audience dissolved into chaos.

Booth, who knew the theater well, quickly made his way backstage to a door which opened onto an alley at the rear of the building. There he expected to find Ned Spangler, with a horse to aid his escape. Spangler had returned to his post as a scene-shifter and left the horse with another stagehand. Booth mounted and sped away into the Washington night. The speed with which he made his escape denies the longstanding tale that he broke his leg when he leaped to the stage from the President’s box, supported by the fact that none of the eyewitnesses reported him limping as he fled. Nor was the banner hung from the box in which he allegedly caught his spur torn, as it undoubtedly would have been.