The North American continent provided opportunity for the curious. The continent had been inhabited by native peoples, but it was not until the 800s when Europeans had primitive means to explore its northern reaches. When shipbuilding and navigational technology improved, ushering in the Age of Discovery, Europeans sailed across the Atlantic Ocean and quickly laid claim to new lands and people. Even after successful settlement, the interior of the continent and its potential for great wealth intrigued men and women that explored the West. Below are 12 explorers and expeditions of North America.

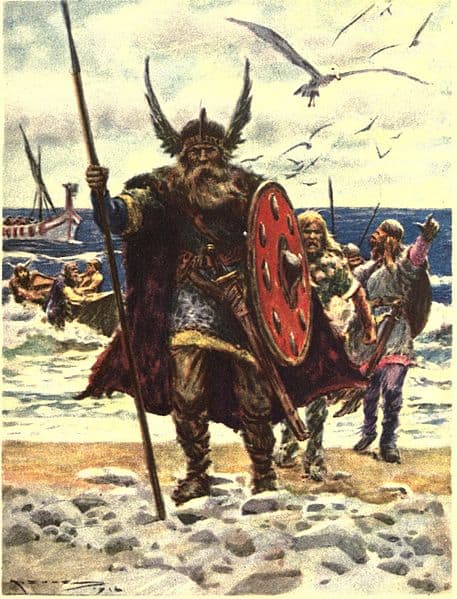

1. Erik the Red and Leif Erikson 980s

Erik the Red, a Norse Viking, killed his neighbor and was banished from Norway. He moved his family west to Iceland. While banished, Erik the Red explored westward and has been credited with establishing the first settlements in Greenland in 986. The Eastern and Western Settlements of Greenland provided the opportunity for Icelanders to leave in search of new farmland.

Erik the Red named the new area Greenland to imply abundant fertile land. Reality was different, but enough Icelanders moved to Greenland to sustain the new settlements. Over time, a central settlement emerged providing food and shelter to people traveling between the East and West settlements.

Leif Erikson, Erik the Red’s son who was 10 years old at the time of his father’s banishment, was also a Norse Viking and explorer. After his conversion to Christianity, Erikson and a crew of about 35 men embarked on a journey to convert residents of Greenland. During a storm, they were blown off course and landed in North America in 1000. The expedition separated into two groups with one exploring the countryside and one creating a permanent settlement.

Erikson named the new settlement Vinland due to its numerous grapevines. Vineland is presumed to be the area that includes Newfoundland, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, and New Brunswick. The Icelandic sagas were literary stories compiled and printed before 1265. The sagas described the Norse exploration of North America. In the 1960s archeological evidence supported the locations described in the sagas, confirming a much earlier arrival of Europeans to North America centuries before Columbus.