The term “Mother Nature” often evokes warm and fuzzy feelings, bringing to mind loving and nurturing images, perhaps of green and grassy fields glistening with morning dew, rippling with the wind sighing through them, as the sun begins its daily journey through the blue skies above.

Or perhaps images of mountain crags overlooking wild valleys, through which rush rivers teeming with salmon, and whose banks are lined with cuddly bears and their cubs feasting and fattening themselves on Mother Nature’s bounty, while majestic eagles soar above, stooping into the occasional dive to strike the water and emerge clutching a wriggling fish in their talons.

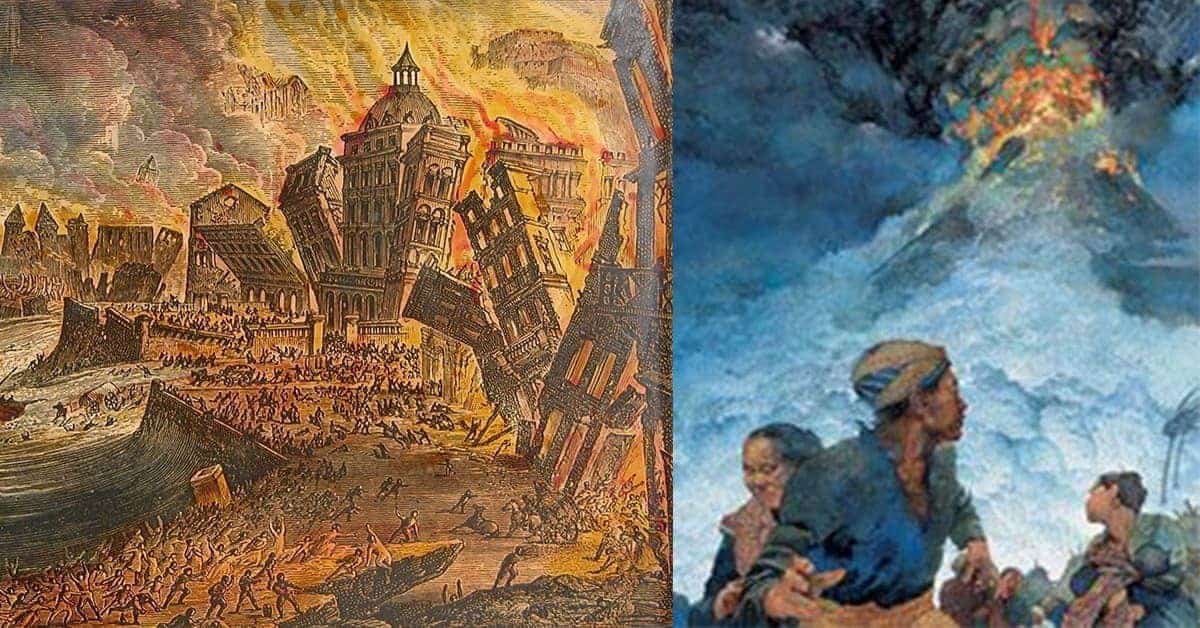

On the other hand, sometimes Mother Nature can be a real mean mother, violent and seemingly psychotic, out to suddenly kill us by the thousands, or even millions, with little or no warning. She does that via natural disasters, sudden events that wreak extensive havoc and widespread devastation, and often significant loss of life as well as great financial loss.

Such natural disasters might result from severe storms, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, flooding, landslides, or any other means of great destruction that are not controlled by human beings or caused by human action.

Following are twelve of history’s most remarkable natural disasters that occurred before the 20th century.

Second Millennium Thera Eruption

The Thera Eruption, circa 1642 – 1540 BC in what is today the Greek island of Santorini, was one of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in recorded history, four times as powerful as the gigantic Krakatoa explosion of 1883. It sundered the island of Thera, and wiped out the flourishing Minoan settlement of nearby Arkotiri and surrounding islands, giving rise to the legend of the vanished civilization of Atlantis, which was doomed by a natural catastrophe and swallowed by the sea.

Beyond legend, however, Thera’s eruption was one of history’s most impactful natural disasters, with consequences not only to its own era but with knock-on effects and a chain of causation leading directly to the world in which we live today.

In addition to the immediate devastation of Thera and surrounding islands, the eruption produced powerful tsunamis that devastated Crete, contributing to the decline of its Minoan civilization and paving the way for its extinction. The Minoans were the Mediterranean’s greatest naval power, as well as the dominant power of the Aegean, including what became Greece and the Greek world.

A trading power, the Minoans were oriented towards Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean and were strongly influenced by those civilizations. While the Minoans flourished, the Aegean world in their thrall was by necessity oriented in the same direction, and strongly influenced by the Egyptian and eastern civilizations as well.

The Thera eruption weakened Crete and the Minoans sufficiently to create a power vacuum in the Aegean, which was filled by the emerging Mycenaeans in mainland Greece. They went on to conquer Crete and destroy the Minoans and became the dominant power of the Aegean. However, unlike the Minoans, the Mycenaeans’ energies were focused not on trade with Egypt and the Levant, but on the Aegean, the western coast of Asia Minor, the Black Sea coast, and would set the stage for future Greek colonization efforts in those regions, as well as the western Mediterranean.

That change of orientation significantly reduced Egyptian and eastern influences upon the Greeks, and when the Greek world flourished centuries later, long after the Mycenaeans had themselves disappeared, it would do so as a civilization and culture distinct from those of Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean, rather than as extension and outpost of those civilizations.

And since western civilization is founded upon that of the ancient Greeks, an argument could be made that today’s western civilization and its impact on the modern world would not exist but for the Thera eruption of the mid 2nd millennium BC.