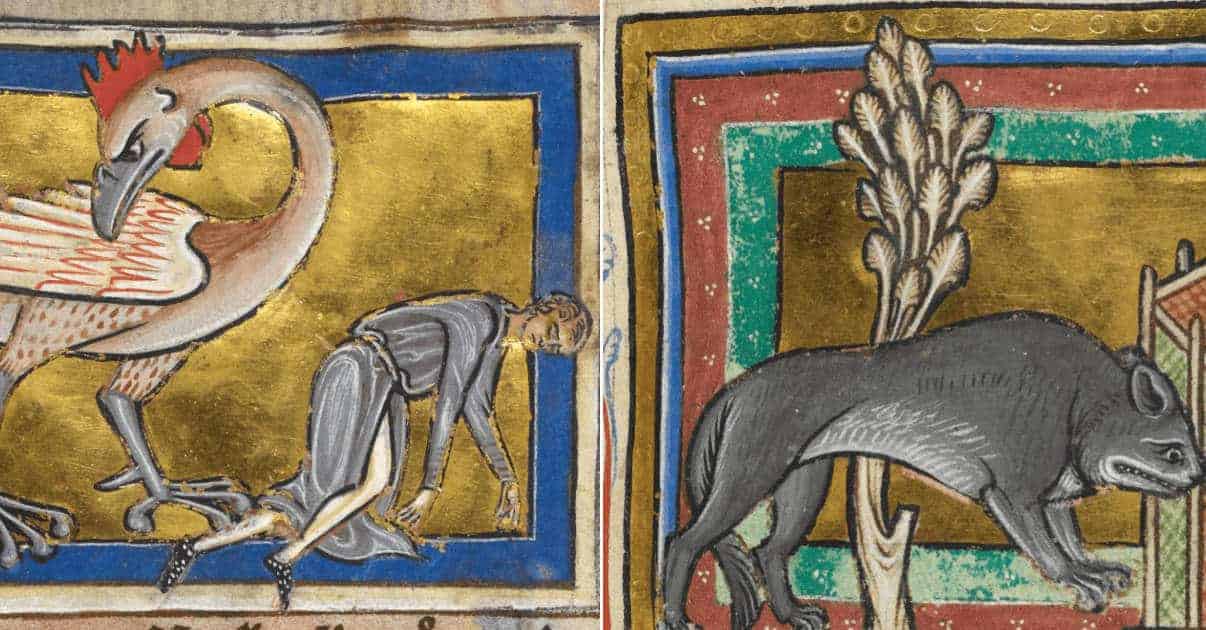

Before the advent of science, those wishing to find out more about the natural world would consult a bestiary. A bestiary was a lavishly-decorated collection of descriptions of animals, real and imaginary, written with the intention of identifying God’s message in the creatures observed in the natural world. This technique of interpretation (not to be confused with pantheism) had a biblical basis: ‘but ask the animals, and they will teach you, or the birds of the air, and they will tell you… In His [God’s] hand is the life of every creature and the breath of all mankind.’ (Job 12:7-10).

The first text aiming to identify the Word of God through the natural world was the Physiologus, a 3rd-century Greek text which proved immensely popular. The Physiologus gave a brief description of each animal before delivering a lengthy didactic interpretation of it. The bestiary of the later medieval period, which we will be discussing here, was a combination of the Physiologus and Isidore of Seville’s more scientific, albeit still erooneous and unreliable, Etymologiae (‘Etymologies’), which drew on older natural history texts such as Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia, and was very much the Wikipedia of the Early Medieval Period.

Bestiaries thus contain information drawn from folklore, popular superstition, and accurate observation alike. Although the descriptions that follow are irrefutably humorous, we must nevertheless remember humanity’s continuing inclination to anthropomorphize nature in order to understand the world better. Birdsong, for example, is still referred to as the ‘dawn chorus’, even though it is a territorial behavior which is more akin to shouting ‘eff-off’ at one’s neighbors. As Disney films demonstrate, we still frequently use anthropomorphized creatures to tell stories and teach morals. As you read this article, therefore, ask yourself this: how different are we from our medieval ancestors?

The Stag

Deer, and stags in particular, have fascinated mankind for time immemorial. From the cave paintings of early man through the horned-helmets of the Bronze Age, it seems that the impressive antlers displayed by male deer have intrigued us most; indeed, the size of a stag’s antlers still determine its value as a trophy-animal, and antlers are a fairly common household decoration around the world. The elusiveness of cervids, too, has lent them an air of mystique, for the Irish referred to them as ‘fairy cattle’. In the medieval period, the stag proved a creature of both sport and Christian allegory.

In the bestiary, stags are natural enemy of snakes. Upon finding a snake’s lair, a stag will first spit into it, then use its breath to lure the creature out (a primitive form of snake-charming). Healthy stags will then trample the serpent to death, whilst elderly or sick stags will eat the snake for sustenance, then drink copious amounts of water to overcome the snake’s poison. They are also proverbially long-lived: Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great put collars around them to show their ownership, and these specimens were found with their collars intact in the late medieval period.

Like horses, you can also find out a stag’s age by their teeth. When crossing water to reach food, stags swim in a line, with each stag’s head resting on the rump of the one in front. When struck by an arrow, a stag can simply shake it out by eating dittany (a kind of herbaceous shrub). Additionally, they are hard to catch because their hearing is very good when their ears are erect, less so when they are prostrate. They can be caught, however, by a hunter playing a pipe, as they are uncommonly fond of music.

They are very wily beasts: upon hearing hunting dogs, stags will change their direction of flight in order to be upwind from the pack. Though stags are lascivious, female deer can only conceive when the star Arcturus has risen. Does give birth solely in thick forest, and teach their young to flee to high places. Venison has medicinal qualities, and protects those who eat it from fever, because stags never suffer from fever themselves. Their antlers can also be burned to ward off serpents, and a concoction made from their tears and heart-bones can cure troubles of the heart.

Allegorically, the stag represents Christ. Like him, they are the enemies of evil, personified by their persecution of, and immunity to, snakes. Their seasonal shedding and re-growing of their antlers also symbolised Christ’s death and Resurrection. Just as eating Christ’s flesh (in the form of the Eucharist) spiritually cleansed participants and protected them from evil, so too the flesh of the stag helped to ward off physical sickness. Their method of crossing a river in a line was also seen as an instruction for Christians passing from this life to eternity: Christians must help one another to reach heaven successfully.