The American Civil Rights Movement was a movement of social reform in the United States that began soon after Reconstruction, and ended, at least in its first phase, in 1964. It was in that year that the landmark Civil Rights Act was passed into law. The main thrust of the protest was equality in society and government for blacks, discriminated against for the centuries of slavery, and then again in the aftermath of abolition. The Civil Rights Act certainly outlawed discrimination in principle, but removing it from the fabric of society would prove much more difficult, and for many, the Civil Rights Movement remains an ongoing struggle.

The Movement, however, was much more than simply the struggle for black emancipation in America. It represents the efforts of any disadvantaged minority, or even majority, to gain equality in life and labor, no matter who or where. Likewise, activism did not always follow the established pattern pioneered by the likes of Doctor Martin Luther King, but took many forms. In this list, we will spread the definition of ‘Civil Rights Movement’ a little bit beyond the orthodox, and examine a view unsung personalities that you might not have guessed were civil rights activists.

Joan Trumpauer Mulholland

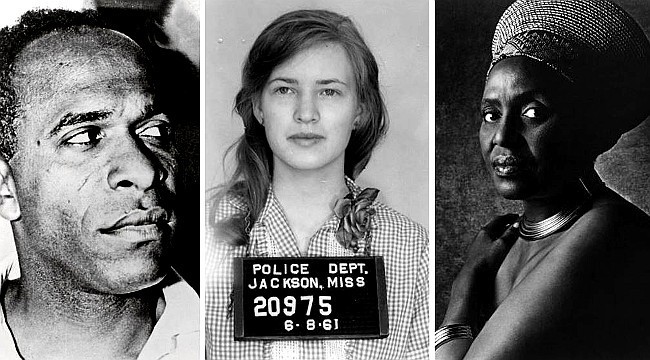

Quite often, iconography is more powerful than law. An image can change the world, and the mugshot of an attractive, homely young white women; dressed in a gingham blouse with a flower pinned to the collar; wearing a look of mild amusement, and filled with confidence is certainly one such image. As one of the ‘Freedom Riders’, Joan Trumpauer Mulholland was arrested in Jackson Mississippi in the summer of 1961, and it was there that this iconic mugshot was taken.

The image is powerful on many levels, displaying on the one hand contempt and defiance in the face of injustice, and on the other the courage of white privilege to make a stand alongside the oppressed minorities. In fact, Joan Trumpauer Mulholland represented a strong corps of affluent, white Civil Rights activists who were very much engaged in the struggle. These were men and women who often suffered not only the cuts and bruises of the front-line, but also being ostracized in their own society, and intense pressures from friends and family.

Joan Trumpauer Mulholland’s activism began when she was a student Duke University in North Carolina, organizing and participating in the sit-ins organized to protest the school color barrier. She was one of only a handful of white activists who were willing to join hands on the front-line, and under pressure from the Dean of Duke Women’s Studies to quit the protests, she instead dropped out and devoted herself entirely to activism. For the most part, this activism took the form of sit-ins, protests, pickets and demonstrations, but also the activities of the ‘Freedom Riders’. The Freedom Riders rode the busses and trains of the South regardless of the rules of segregation, and in fact it was this that ended in her arrest, and a two-month prison sentence.

Then John Trumpauer Mulholland made a powerfully symbolic move, and as black students were enrolling for the first time at Georgia University, she enrolled at the black Tougaloo Southern Christian College in Mississippi. Along with her fellow students at Tougaloo, she participated in the famous Woolworth sit-in. The episode turned violent, and Joan was brutally manhandled in full view of police and FBI. She stayed on the front line, however, and is still on the front-line today.