Sir Francis Galton was a Victorian polymath and a cousin of Charles Darwin. A prolific writer, he produced over 350 books and academic papers over a lifetime which spanned 88 years, including the Victorian era. Among his many gifts to humanity, one finds the modern weather map, the Galton Whistle test for the measurement of hearing ability, the best technique for the proper brewing of tea (or so he claimed), and a method of classifying fingerprints, creating categories of types which helped lead to their full acceptance by courts of law. He also coined the word “eugenics” to define his theories on improving the human race through the use of selective breeding.

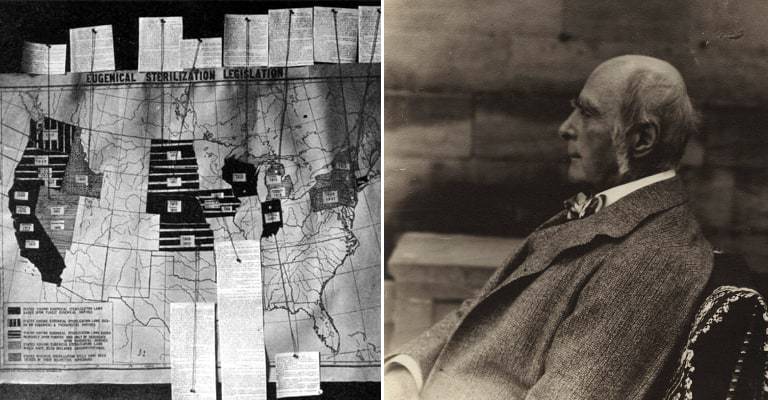

Eugenics found a following in Victorian England, which spread through Europe and across the Atlantic to the United States. It became highly politicized in America, with some groups designated as being less desired members of society which should be restricted from reproducing. Other groups were designated as being highly beneficial to the betterment of humanity and thus encouraged to reproduce. Several US states enacted and enforced sterilization laws. Not until the end of the Second World War did the practice of eugenics fall into widespread disfavor, and then only because of the argument by war criminals at Nuremberg and other trials claiming similarities between the Nazi eugenics programs and those of several other countries, including the United States.

Here are some examples of Eugenics programs in the United States which existed in the not-so-distant past.

The Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924

It was not the first legal action by a state to order the enforced sterilization of what the state deemed to be undesirables. Fifteen states preceded Virginia in enacting such laws. Virginia was the first to enact the law in recognition of what the legislature termed an “emergency existing” and the first to rigidly enforce the law. Between its enactment in 1924 and its withdrawal in 1974 more than 7,000 human beings were forcefully sterilized under the law. Virginia also established and enforced rigid requirements for marriage. An individual could be subject to forced sterilization for epilepsy under the law, and many were.

At the same time, the Virginia legislature passed the Sterilization Act it also passed the Racial Integrity Act, which expanded the state’s anti-miscegenation laws which had existed since Virginia’s colonial era. Using the theory of eugenics as justification, the legislature divided the population of the state into two races, white and colored, and forbade marriage between them. The American Indians residing in the state were classified as colored. The legislature adopted what was called the one drop rule, an allusion to one drop of blood, which stated that any trace of colored blood in a person’s ancestry rendered that person colored.

This posed a problem for many of the oldest Virginia families. Called the First Families of Virginia, many of these members of the social elite of the state and the several branches of their family trees could trace their ancestry back to Jamestown, and descent from the family of John Rolfe and his wife Pocahontas. It was a sign of social standing and significance to be able to do so in Virginia. The legislature responded by amending the act to accommodate those claiming relationship to Pocahontas and other American Indians of colonial days to allow for those who could claim up to one-sixteenth Indian ancestry.

Eugenicists, who claimed as their motivation the improvement of the human race through implementing the studies of Darwin and Galton were unhappy with the exception to the Racial Integrity Act and worked over the years to tighten the restrictions it imposed. They also worked to enact local laws to tighten the enforcement of both acts. The remaining American Indians found that their population would be reduced simply by the classification of descendants as colored rather than as Native American.

Sterilization under the Racial Integrity Act was not authorized, but eugenicists who worked towards racial sterilization could and did use the Sterilization Act to accomplish that goal in some cases. The Sterilization Act authorized the mental health institutions to sterilize those deemed “feeble-minded” a deliberately vague term covering a broad category of persons who could be so designated. The Virginia registrar of statistics, Walter Plecker, in enforcing the Racial Integrity act in the 1930s, corresponded with Walter Gross, the director of the Bureau of Human Betterment and Eugenics in Nazi Germany, expressing a wish for stronger laws in Virginia.