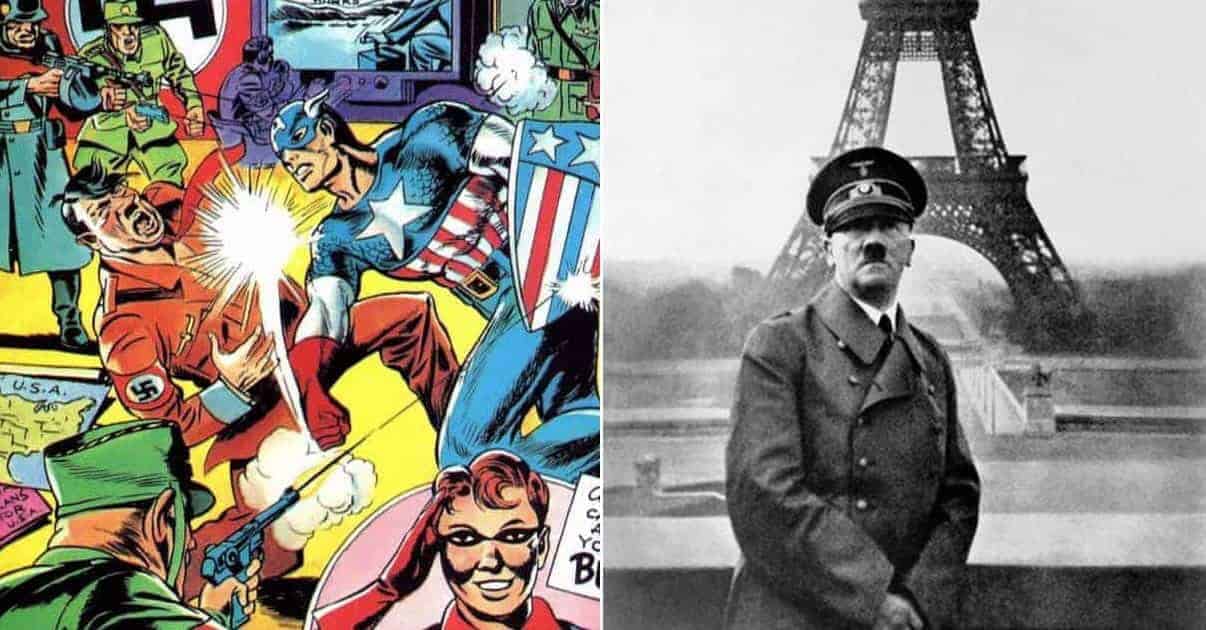

Few people in history deserved to have somebody stick it to them as much Adolph Hitler deserved it. In the grand scheme of things, fate itself stuck it to Hitler in the end, and did so in a big way. He spent his final days ranting out his rage, hunkered in an underground bunker while his enemies closed in on him from all sides. His vaunted so-called “Thousand Year Reich” had lasted barely a dozen years before collapsing. His dreams of lebensraum and seizing a vast empire in the east from Slavic and Asiatic so-called untermenschen, had vanished in the mist.

He once had a vision of exterminating most Slavs and Asiatics east of the Urals, and enslaving the survivors to serve his German so-called “Master Race” as helots. Instead, by April of 1945, those Slavs and Asiatics, in Red Army uniforms, were rampaging through his capital and reducing it to rubble. Utterly defeated, with his dreams in ruins and his empire reduced to a smoldering wreck, Hitler took his own life. However, before reaching that pathetic end, Hitler had once been an extremely powerful and frightful figure. Nonetheless, even when he was at the height of his power, brave and enterprising people did stand up to the Fuhrer and stick it to him.

Following are ten examples of people who thwarted Hitler and stuck it to him.

German War Hero Tells Hitler to Go F*ck Himself

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870 – 1964) was a Prussian army officer who rose to the rank of general in Germany’s Imperial Army. When World War I began, he was the military commander in the German colony of Tanganyika – today’s Tanzania. He knew that his colony, and all of East Africa, would be a sideshow. So von Letow decided to aid Germany’s war effort by tying down as many British troops as he could, in order to keep them away from other fronts more vital to Germany.

He succeeded beyond his wildest expectations. In what came to be known as the German East Africa Campaign, von Lettow led his forces and kept them in the field against great odds. He never had more than 14,000 men – 3000 German and 11,000 African natives – but still managed to keep in check British, Portuguese, and Belgian armies that numbered nearly half a million men.

Despite the great disparity in numbers, von Lettow harried his opponents and led them on a merry chase throughout four years of war, conducting one of the greatest guerrilla campaigns in history. He remained undefeated throughout the war, and only gave up the fight at war’s end after Germany threw in the towel and signed the Armistice of November, 1918.

Von Lettow’s exploits earned him the affectionate nickname The Lion of Africa. After the war, as his country’s only undefeated commander, he returned to a hero’s welcome in Germany. Von Lettow became active in politics, and as the Nazis rose to power in the tumultuous years following Germany’s defeat in WWI, he attempted to establish a viable conservative opposition to Hitler.

Von Lettow’s efforts failed, and Hitler came to power in 1933. In 1935, seeking to exploit the high respect and esteem in which Von Lettow was held by his former British enemies, Hitler offered to appoint him the Third Reich’s ambassador to Great Britain. Von Lettow not only declined, but in no uncertain terms told Hitler to “go fuck himself”.

Unsurprisingly, that insult did not sit well with the Nazis. From then on, they kept him under close surveillance, repeatedly searched his home, and kept harassing him during their years in power. The only thing that saved him from being sent to a concentration camp was his immense popularity with the German public as a genuine national hero, who represented one of the few bright spots in an otherwise dismal WWI.