The American Civil War was notable for the savagery with which Americans slaughtered each other. Historians have long blamed the generals who used tactics devised in a day of less-lethal weaponry for generating up to then unheard of casualty figures, but outdated tactics are only a part of the story. The Civil War presented American sectional prejudice to the world in a new and previously unseen light.

Part of it was the harshness of the times. An attitude of fatalism prevailed. Diseases which are now considered routine were often fatal. The soldiers which filled the ranks of both armies were subject to poor diets, often malnourished, with dental diseases an accepted though dangerous fact of existence. The men wore heavy woolen clothing in the hellish subtropical climate of the American South, practiced poor hygiene and sanitation, drank fetid water from often unhealthy sources, and consumed poorly preserved foods.

The average life expectancy for a man in 1860, the year before the Civil War began, was forty years. Death was a familiar event, virtually everyone had felt the loss of loved ones at a personal level. Killing the enemy meant winning the war and going home, and the soldiers of North and South killed as many as they could, whenever and wherever they could.

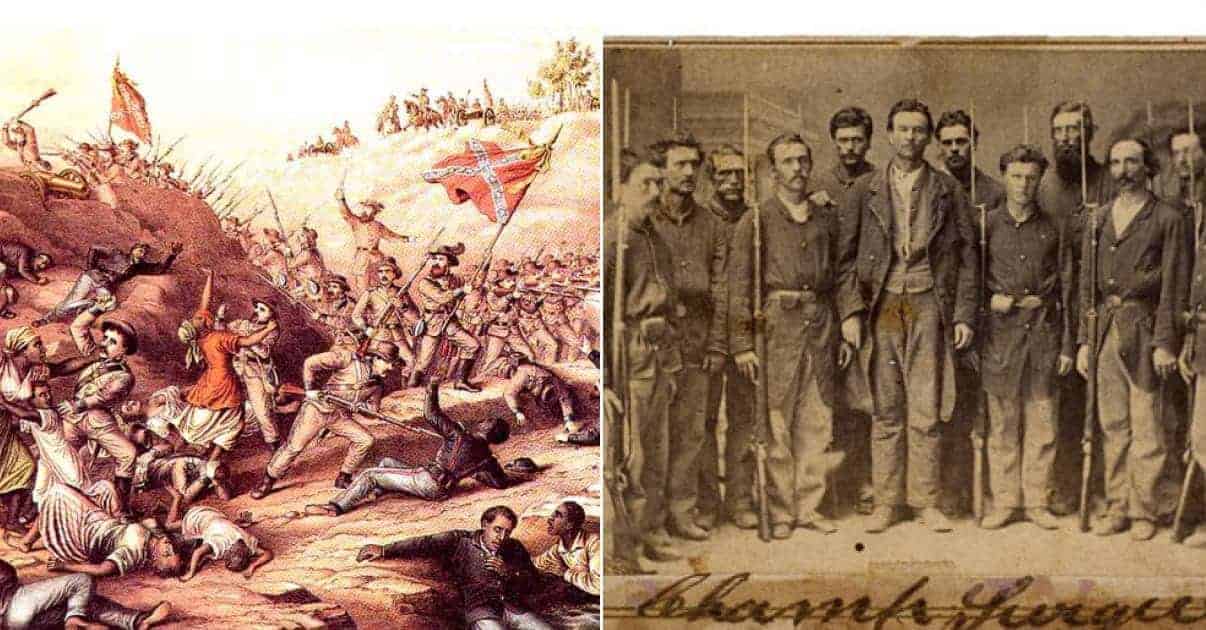

There were instances in the great crime of national destruction which exceeded the accepted bounds of war, crimes against nature and nature’s God. Here are ten instances of Civil war events which today would be considered war crimes.

The Great Hanging. Gainesville, Texas 1862

A sometimes forgotten aspect of the American Civil War is that not everyone in the Southern States supported the idea of secession, nor owned slaves. Some actively opposed the idea of going to war to preserve the institution of slavery, others simply tried to go about their daily lives while ignoring as much as possible the chaos from the war. To the active secessionists, these citizens were called “Unionists” and the Confederacy passed laws to identify them, and restrict their behavior. Many were imprisoned and their property confiscated.

Cooke County Texas had opposed secession at the ballot box with over 60% of voters expressing the desire to remain in the Union. In early 1862 the Confederate Congress passed the first of a series of Conscription Acts, which many of the citizens of Cooke County opposed, having no desire to serve in the Confederate Army. When some citizens announced the formation of the Peace Party to formally protest conscription, Texas troops of the Confederate Army – still a largely volunteer force of pro-slavery troops – arrested over 150 citizens under suspicion of colluding with the Union.

A hastily convened court of pro-slavery members began trying the prisoners, outside of Texas law, at first requiring only a simple majority of the twelve jurors to obtain a conviction. After several convictions, the court changed its rules to require a two-thirds majority. At the same time, vigilante groups continued to round up those suspected of Unionism. Some units of the Texas militia attempted to stop what had become mob rule leading to a Colonel of the Texas militia being killed during the pursuit of a suspected Unionist. Outrage among the slave holders and their supporters led to previously acquitted Unionists being retried and convicted.

Most of the Union supporters – who were really nothing more than draft resisters opposed to wealthy slave owners being exempted from conscription – were executed by hanging. More than 40 were hanged at Gainesville, others were shot, some while reportedly trying to escape. Public sympathy and the press were mostly supportive of the trials and hangings.

The Confederate government turned a blind eye to the trials and executions, which were stopped when the State of Texas, under its new Constitution, took jurisdiction and dissolved the courts. Changes to the conscription laws altered the exemptions, and those supportive of the Union wisely became less vocal. In Texas today the state maintains a historical marker celebrating the hangings, which identifies the victims as traitors.