A utopian community is often considered to be a simply perfect place to live, free of danger, a modern equivalent to the Eden described in the book of Genesis. This perception is wrong. The word utopia was used in the title to a book written by Sir Thomas More which described an island nation and satirized the Catholic Church, Protestant theology, and lawyers (The full title of the book translated from Latin is A Truly Golden Little Book, No Less Beneficial Than Entertaining, of a Republic’s Best State, and of the New Island Utopia). The word was formed from Greek and literally translated means no place. In modern usage the word utopia is generally considered to be a place which is better than any found in contemporary society and which is thus non-existent.

Many efforts have been made in the past to create utopian communities, isolated from the contemporary society they were created to escape. Some have been created for the purpose of unfettered worship, others for the purpose of living in complete harmony with nature, still others to experience a completely egalitarian society. Many so-called hippie communes attempted to achieve a utopian society in the 1960s, nearly all of them were short lived. Besides the works of Plato and Sir Thomas More there is a long list of utopian society in literature, including Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Men Like Gods by H. G. Wells, and Andromeda, by Ivan Yefremov.

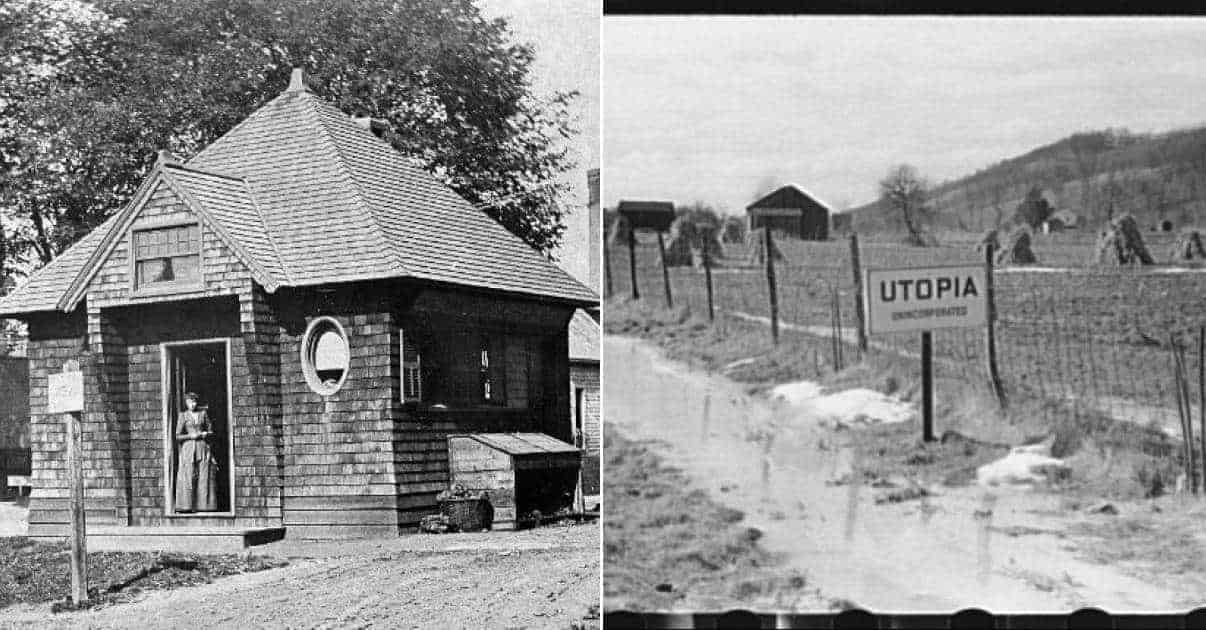

Here are the brief histories of ten utopian communities in the United States.

Brook Farm, Massachusetts

The philosophy of transcendentalism began to develop in New England in the late 1820s, as an argument against the rise of both spiritualism and intellectualism. Its supporters believed that human beings are inherently good, and the trappings of society corrupted them. Transcendentalists believed that humans find their true selves through intuitive means, and reach their best when they are completely self-reliant.

George Ripley, a Unitarian minister, and his wife Sophia embraced the philosophy and in 1841 established Brook Farm as a joint stock company about ten miles outside Boston in West Roxbury. In essence, the joint stock arrangement meant that participants in the community would share in the work as well as the profits generated by the farm. Each member would choose whatever work they wished, including women, and each member would be paid equally. Visitors to the farm paid a fee, which was added to the community funds from which everyone was paid.

A school system established on the farm created income through outsiders’ attendance, but the farm itself was not profitable. By 1844 the members were operating under the socialism promoted by Charles Fourier and published a newspaper called The Harbinger promoting what they Fourierism. The members began the construction of an enormous community building called the Phalanstery, which would house all indoor activities for the community. It was destroyed by fire.

Following the expense of building the Phalanstery and its destruction (it was uninsured) the community collapsed financially. It gradually shut down and was completely closed by 1847. One of the community’s founders was novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, who invested in the community despite not being a strict follower of their beliefs. Hawthorne used the experience as the basis for the novel The Blithedale Romance.

The remaining buildings and property were taken over by the Lutheran Church, which used the property as an orphanage and school for well over a century. Many of the original buildings were eventually destroyed by fire. The farm is today operated as a historic site by Massachusetts.