Queen Victoria gave her name to the entire era of British history and presided over a period in which Britain moved from a predominantly rural society to the world’s leading industrial nations, from one of several European powers to the single predominant force on Planet Earth.

She was one of the longest reigning monarchs of all time, the second longest serving British royal and indeed, Queen Elizabeth II only overtook her earlier this year. Her long life, however, was hard-fought: few figures in history – OK, Castro – can have endured as many assassination attempts as the “grandmother of Europe” suffered in her 81 years.

Certainly, if there was a golden age of assassination, the late nineteenth century was it. Some of the major royals of the period were killed as radical political movements such as socialism and anarchism, with their visceral hatred of monarchy and the established hierarchy.

Alexander II of Russia – a great friend and dancing partner of Victoria when they were young – was blown up by members of the People’s Will revolutionary group (including Lenin’s brother) while Empress Elisabeth of Austria, with whom she was also friendly, and Umberto I of Italy were both also killed by anarchists.

Queen Victoria, however, survived at least 8 attempts against her life: let us talk you through them.

1 – Edward Oxford, June 10, 1840

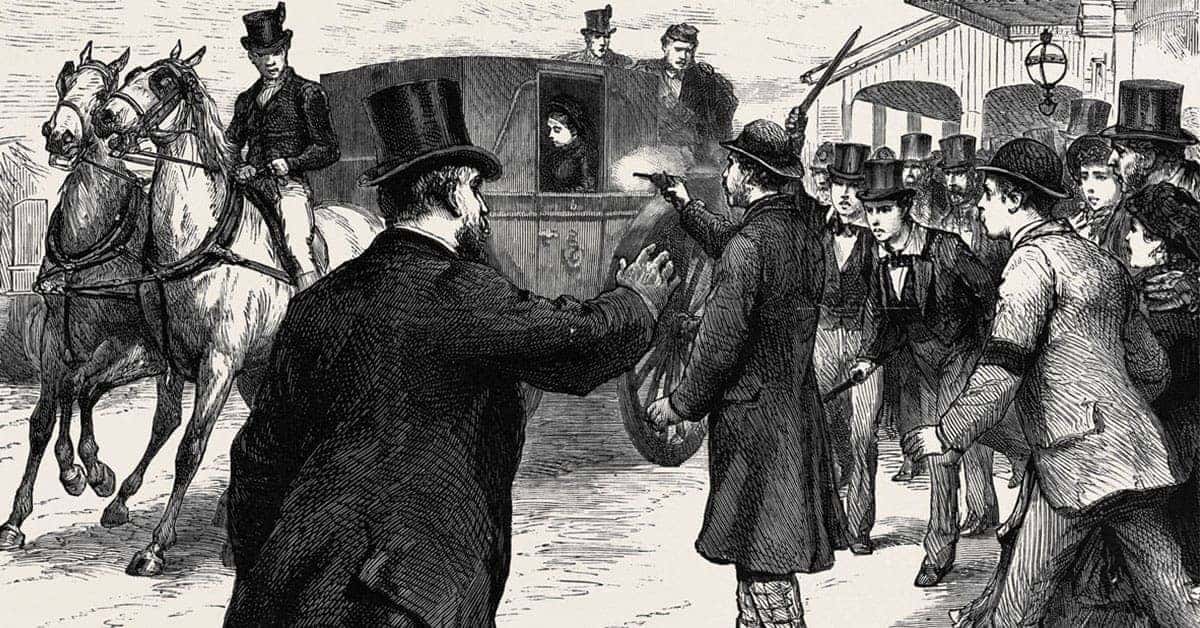

The first hit came just four months after Victoria’s wedding to the German Prince Albert. As the Queen and her husband were traveling in the royal carriage through London, Albert noticed what Victoria later described as “a little mean-looking man holding something toward us.”

That man would turn out to be Edward Oxford, a teenage barkeeper. The thing that he was holding was a dueling pistol, which he fired in the direction of Victoria, who was heavily pregnant with her first child, Victoria, the future Empress of Germany. Despite standing within 5 meters of the royals, Oxford managed to miss with his first shot and by the time he got a second away, the Queen was able to duck.

Amazingly, the royal couple continued their trip. “We took a short drive through the park, partly to give Victoria a little air, partly also to show the public that we had not, on account of what had happened, lost all confidence in them” Albert later wrote.

The planning that had gone into the attack was meticulous. Oxford had been living alone for a month – his mother, whom he usually shared the home with, was away visiting relatives – and thus had the whole house to turn over to his scheme. He bought two pistols and began attending a shooting gallery to hone his skills. At the beginning of June, Oxford purchased 50 percussion caps – a vital piece of equipment when firing a Victoria-era gun – from an old school friend, as well as powder for the gun. He later sourced bullets.

Once he had fired at the pregnant Queen, Oxford was immediately jumped upon by bystanders and accosted. He put up no fight, declaring “It was I, it was me that did it.” The police arrested him and searched his residence, finding swords, guns, bullets and the percussion caps that he had recently bought. They also found self-penned political literature regarding a group that, on further investigation, was found to be a fabrication of the assassin’s imagination.

Oxford was charged with treason, but it was to later found not guilty on grounds of insanity., Once he had been declared insane, Oxford was committed to a mental asylum for three years before finding himself, as so many did, transported to the colony of Australia to see out his days.