Teddy Roosevelt was not known for being demure. Nor was he known for small thinking or insignificant actions. He was a man who fearlessly charged San Juan Hill. He was a man who often disappeared alone into the vast American wilderness in order to fortify his spirit. He was a man who was shot in the chest and refused to go to the hospital, instead insisting on completing a scheduled speech.

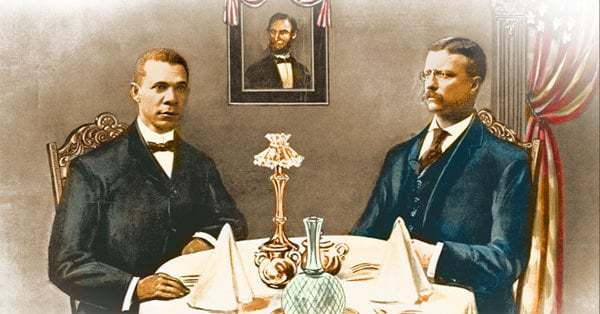

What bold action was it then, which prompted a Tennessee newspaper to proclaim that Roosevelt committed “the most damnable outrage which has ever been perpetrated by any citizen of the United States”? It was a simple dinner invitation – a public invitation to formally dine with Booker T. Washington, in the White House.

It can be written with certainty that in 1901, when the invitation was offered, Booker T. Washington was one of the most respected African Americans in the United States. He was appreciated by many Southern traditionalists and a favorite of Northern progressives alike. He was a self-made man, born a slave but with an unappeasable hunger for education and boundless work ethic, became a social healer and black icon to many during the turn of the 20th Century. So why did a simple dinner invitation given to an honorable and popular man like Washington cause such a scandal?

While a modern reader can appreciate how prejudiced feelings may be awoken by those in support of racial segregation, the depth of the passions this event evoked can be hard to appreciate today. Many were outraged, not just because the President of the United States invited a black man to dinner, but that it was publicly acknowledged, held at the White House, and Roosevelt’s family were present. All of these elements were deeply symbolic. Today, dining is usually a very casual event, but during the turn of the 20th Century, inviting a man to your dinner table was an action heavily filled with social significance.

In the early 1900s people still tended to dine only with those they considered equals, or at least with those considered to be colleagues in some meaningful way. A dinner invitation could even be considered an invitation to sexual access. In some parts of the country, a single man invited to sit with the head of a family for dinner could be seen as an invitation to court his unmarried daughters. Though Booker T. Washington was a married man, such cultural knowledge made many feel a deep sense of unease.

Allowing Washington to formally sit at a table with his wife and children was an outrageous act to many. The Richmond Times could not be clearer when it described what the consequences of this seemingly harmless dinner really signified. “It means that the president is willing that negroes shall mingle freely with whites in the social circle – that white women may receive attentions from negro men; it means that there is no racial reason in his opinion why whites and blacks may not marry and intermarry, why the Anglo-Saxon may not mix negro blood with his blood.”

A newspaper out of Missouri published a poem with an explicitly racist title suggesting that members of the Roosevelt and Washington family should intermarry, now that such a dinner took place. An excerpt from the poem concludes:

“I see a way to settle it

Just as clear as water,

Let Mr. Booker Washington

Marry Teddy’s daughter.

Or, if this does not overflow

Teddy’s cup of joy,

Then let Miss Dinah Washington

Marry Teddy’s boy.”