American history is full of firsts – it befits a nation as young as the United States – but few lasts. If if you’re a Native American, however, you might see that statement completely the other way around. If you were Ishi, the last of the Yahi tribe, you almost certainly would see it that way.

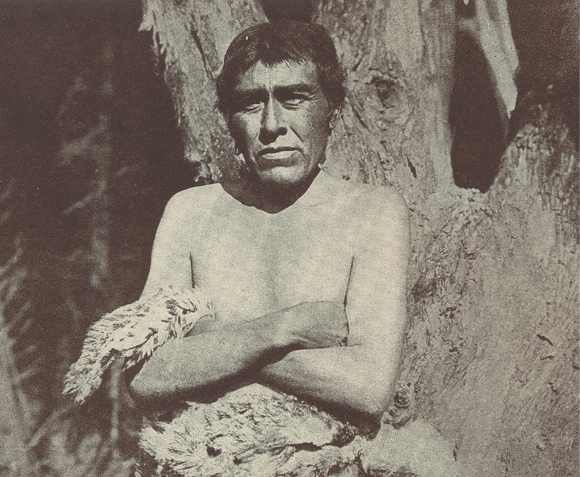

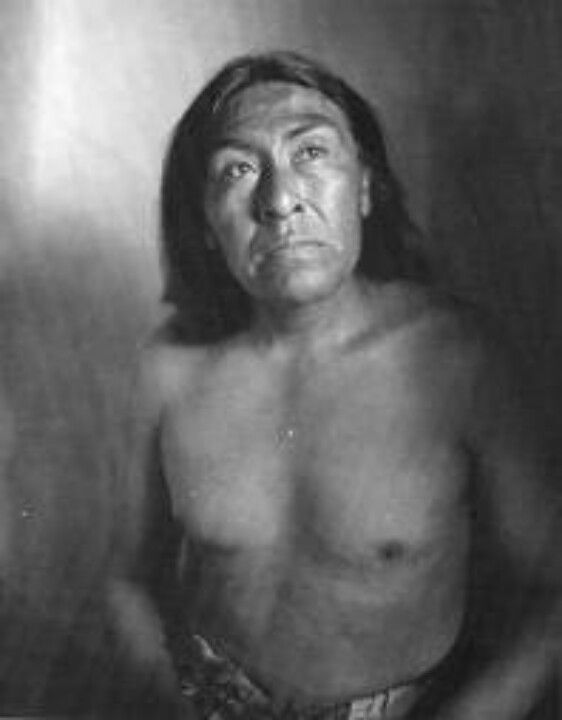

Ishi was the final Native American to live without European contact, something that he managed for the vast majority of his life. Born in the wilderness interior of California during the Civil War era – his exact birthdate is unknown – and raised as a member of the Yahi tribe, Ishi’s early life was a microcosm of the early American colonization of the West.

His tribe were massacred, their land forcibly taken and their livelihood decimated. Alienated from anyone who spoke their language and unable to practice their culture, the Yahi lived nomadically in the huge forests of the Californian hinterland, surviving on the few deer remaining to hunt and their extensive knowledge of their environment. They avoided contact with the white man, an aversion based on well-founded fear. Gradually, as members of the group died off, the man who came to be known as Ishi became the last of his tribe.

The circumstances of Ishi’s life cannot be separated from the history of Native Americans in the western United States. Prior to European contact, the Yahi people were just one of the larger group of Yana that inhabited the areas of Northern California around the Sierra Nevada, living on the plentiful fauna of the forests and the vegetables that could be harvested from their environment. Anthropologists chart their numbers in the late 18th century as being around 1500-2000 individuals, scattered in small groups that roamed between the Yuba and Feather rivers, not far to the north of what is now Sacramento.

Before Ishi was even born, the writing was on the wall for his people. The defining moment in the history of the Yana would take place in 1848, when gold was discovered in the town of Coloma, some 100 miles to the south. Once it had been announced to the US Congress in late 1848, 300,000 people arrived in California – which was at the time not even a state – within a year to seek their fortunes mining gold. The “Forty-Niners”, as they were known, completely changed the demographics of the area from predominantly Native American, californios (Spanish-speaking settlers) and a smattering of White missionaries and agricultural farmers to a free for all of Americans, Chinese, Europeans and Latin Americans.

There was, unsurprisingly, little place for Native Americans. When the first round of easily attainable gold was gone, the prospectors moved further into the mountains, seeking their fortunes upstream. The indigenous residents of these areas were paid little heed when there was gold at stake: they attempted to resist but, lacking guns, were massacred consistently.

To compound that, the Forty-Niners brought a whole host of diseases with them to which the Yana had no immunity. The salmon of the Yuba and Feather rivers, from which they had derived food for generations, was taken too. A population that was estimated at 3,000 in 1848 was reduced to barely 400 by Ishi’s birth in the early 1860s. It was into this maelstrom that Ishi was born.