Mary Bowser is not a name you will easily find in the history books. Her name will not be a familiar one because she used many in her life. Like a true chameleon who became a spy during the Civil War, she lived her life close to the shadows, wearing many faces, concealing her true nature until it was needed. It has been challenging to reconstruct the events in Mary’s life because so much of the information that surrounds her is legend. The gaps in the historical record because of her color and gender leave room for interpretation and assumption.

Mary’s true identity as a member of Elizabeth Van Lew’s spy ring the Richmond Underground wasn’t confirmed until 1900, by Van Lew’s niece, almost forty years later. Another member of the spy ring, Thomas McNiven, mentions Mary in his memoirs, but it is an oral history that wasn’t officially written down until the mid-twentieth century. Such records are rarely accurate. Some sources argue that she didn’t exist at all.

Born a slave in 1840s Virginia, her presence in the historical record is brief but eventful: she received an education, served as a missionary in Africa, and worked as a teacher for the Freedmen’s Bureau. Mary’s most compelling role was that of a Union spy during the Civil War, working with her former owner Elizabeth Van Lew’s Richmond Underground spy ring. She was Elizabeth’s most valuable asset, working in the Confederate White House so she could gather information on the movements of Confederate troops. It was a dangerous mission, but Mary was well-suited to the role.

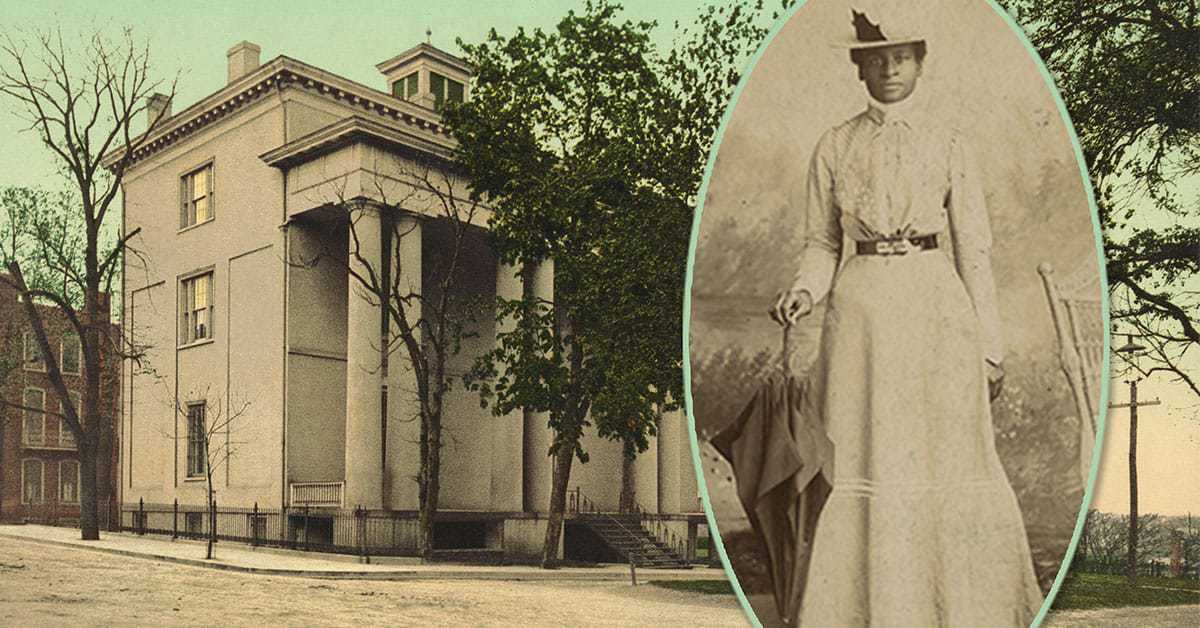

Mary Bowser was born in 1841, owned by the prominent Van Lew family, a prominent upper-class family in Richmond, Virginia. Very early on, the Van Lews favored Mary. They baptized her in Saint John’s Church in Richmond, not in the First African Baptist Church where they usually baptized their slaves. Recognizing her potential, the Van Lew’s daughter Elizabeth freed Mary in the late 1840s and brought her North for an education. After her training was complete, Elizabeth wanted Mary to travel abroad to the newly independent Liberia to teach as a Christian missionary.

On December 24, 1855, the fourteen-year-old Mary joined the American Colonization Society on a missionary trip to Monrovia, Liberia. According to Elizabeth’s correspondence, Mary was unhappy in Liberia and wanted to come home. Elizabeth made all of the arrangements for her return, even going so far as to arrange it with the American Colonization Society to make sure that Mary came back in a first-class cabin. An indication of how much Elizabeth cared for her charge, she wrote, “I will try to do the best I can by her – as I would be done by…I do love the poor creature – she was born a slave in our family – & that has always made me feel an awful responsibility.”