“Anastacia” Anastacia, holy Anastasia,

You who were borne by Yemenja, our mother,

Give us the strength to struggle each day

So we may never become slaves,

So that, like you, we may be rebellious creatures

May it be so. Amen” (Popular prayer to St Anastacia)

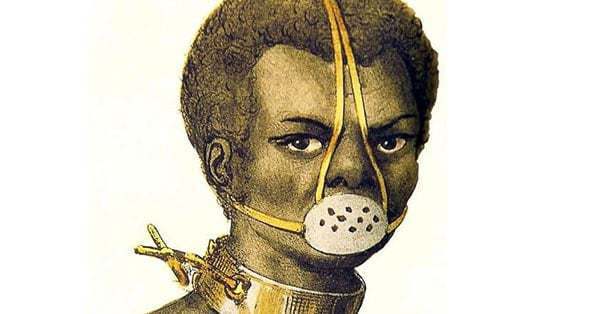

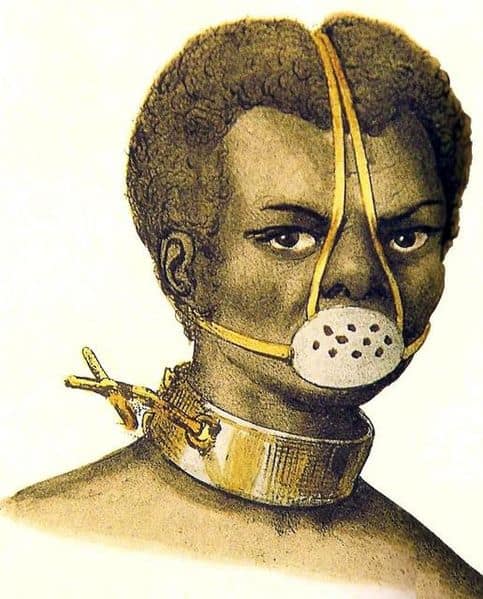

The figure of St. Escrava Anastacia -“Anastasia the Enslaved”- is a mysterious one. Portrayed as an African slave woman, her piercing blue eyes, collar and cruel, muzzle-like facemask define her image. Facts about Anastacia’s life are scant. According to what we know of her, she was an enslaved woman of African descent, cruelly muzzled by her masters.

But today, she is an iconic figure in Rio in Brazil- a popular, if unofficial saint of the Catholic church, as well as the Umbanda, an African-Brazilian religion, and the Brazilian Spiritist traditions. Her cult resonates not just amongst the Afro-Brazilian population and the poor but also with people from a wide variety of backgrounds.

Was St. Anastacia a real person? And why has she won the hearts and minds of the people of Rio?

A Blue Eyed Slave of African Descent

All the evidence of Anastacia’s life is essentially oral and she cannot be verified as a real, historical person. But, like all oral history, there is some basis in fact. There are essentially two tales of St Anastasia’s life. One places her birth in Africa, the other in Brazil itself.

In version one of Anastacia’s story, she was born in Africa, a Royal Princess who was enslaved and shipped to Brazil. According to Carlos de Lima, a Brazilian historian, the enslaved Princess became a housekeeper on a sugar came plantation.

In the second version, Anastacia was the child of a black, female slave from the west coast of Africa. Her mother was raped by her owner- and Anastacia was the result -the first black child to be born with blue eyes. The plantation owner had the baby sent away, to hide the evidence of his ‘infidelity’ from his wife.

This Anastacia can be linked to Delminda, a daughter of the royal family of Galanga of the Bantu tribe in southern Nigeria. Delminda was one of a cargo of 112 slaves shipped to Brazil in 1740. She was sold in the harbor on arrival to Antonio Rodrigues Velho, who then raped her and sold her on to Joaquina Pompeu. On the 5th March, Delminda reputedly gave birth to a blue-eyed baby girl -one of the first female black slaves to have this feature.

The Girl in the Iron Mask

Like the stories of her origins, the reasons Anastacia’s masking also varies. In the Delminda story, Anastacia grew up to be extremely beautiful and Joaquin Antonio, her owner’s son became obsessed with her. The free women of the plantation were jealous of her beauty so they persuaded Joaquin to put her in an iron mask that covered the lower half of her face. This Joaquin was happy to do as Anastacia was fighting his advances. Once masked, he raped the object of his passion and only allowed her to take the mask off once a day in order to eat.

In the de Lima story, Anastasia the princess was masked for teaching her fellow slaves to worship their native African gods under a thin guise of Christianity. The muzzle-like mask prevented Anastasia from speaking and so corrupting her fellow slaves.

What both stories agree on is, despite her cruel ill-treatment, Anastacia was an inspiration to the other slaves. She bore her misfortune with fortitude, healing the sick and inspiring hopes for freedom. She did not fight against the slave mask -which must have been extremely uncomfortable at best, torturous at worst but instead treated everyone with calmness, kindness, and love. She forgave her cruel masters, even going so far as to heal her mistress’s son.

Either way, the stories say Anastacia met a tragic end, dying of tetanus caused either by the mask or the collar she was forced to wear. Her owner posthumously freed her and she was buried in a slave cemetery in Rio. Her remains were said to be housed in the Church of Rosario, which was burnt down in 1967.

While examining the ruins of the burnt church in 1968, investigators found an engraved portrait of a blue-eyed black woman, collared and in a mask at the back of the church. The artist was the French watercolorist Etienne Victor Arago and the picture was produced sometime in the early nineteenth century. Immediately, the picture was associated with the legend of Anastasia.