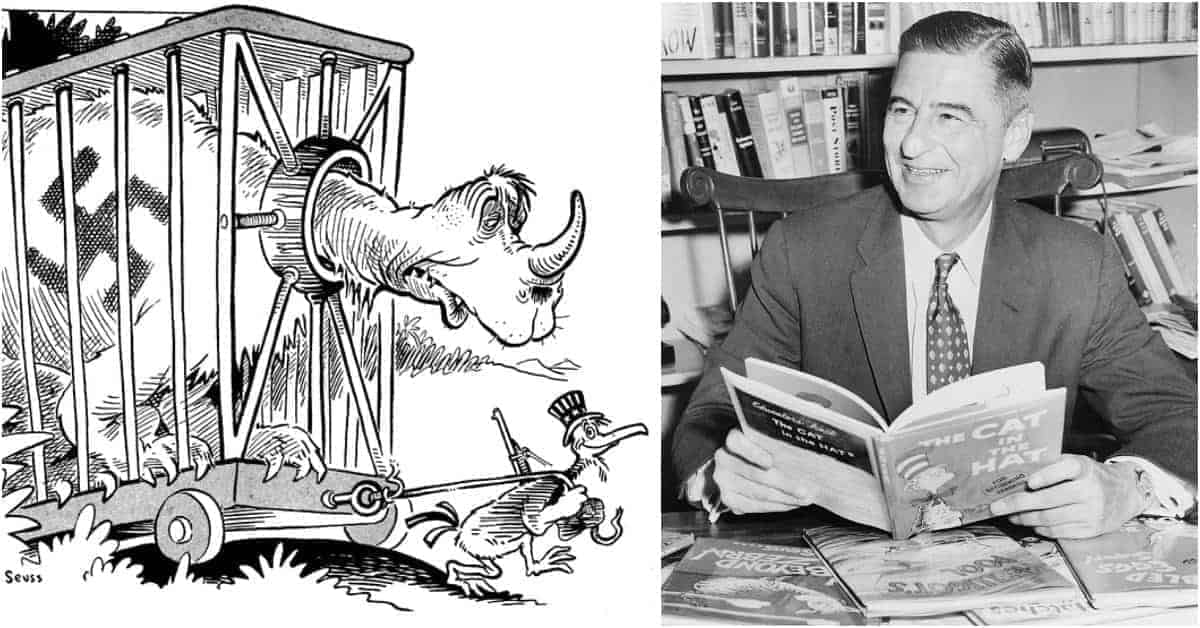

Dr. Seuss is a household name around the United States, and his iconic children’s books from the 1950s continue to be used in elementary and preschools around the country. What is not as well known, however, is that before he took on the persona of Dr. Seuss the beloved children’s author he was Theodor Geisel the World War II propagandist.

As the editorial cartoonist for the New York newspaper PM between 1941 and 1943 he published cartoons aimed at mobilizing the American people to fight and win the Second World War, but his work from this period also reflected some of the darker sides of wartime American society. What follows are ten of his most distinctive cartoons of the era.

On September 30, 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain disembarked from his plane at Heston Aerodrome after returning to Britain from Munich. Bearing an agreement signed by Adolf Hitler, he addressed the assembled crowd to ensure them that he had secured “peace for our time.” Ever since this statement has stood as the ultimate expression of the naivety of the policy of appeasement: the idea that an aggressive foreign power might be soothed by giving in to some of its demands.

At the heart of the drive for appeasement was the lurking trauma of the First World War. The horrors of the trenches had hardly faded in the intervening two decades, and the great powers of Europe had no desire to see their children reenact the carnage. Hitler, however, was able to take advantage of this reticence to return to war.

France had stood by when Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland in 1936. Chamberlain had flown to Munich to trade the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia to Germany in exchange for peace in September 1939, and no one intervened when the Wehrmacht rolled into the remainder of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

In this cartoon, Geisel comments on the lunacy of the policy of appeasement. At the center stands a balding figure marked “The Appeaser,” who gazes amiably at a collection of sixteen toothy sea monsters clad with swastikas, one of which appears to be an early rendition of the Grinch. The caption, “one more lollypop, and then you all go home” may as well be the mantra of appeasement. The cartoon’s audience must surely see that the beasts have no intention of leaving until they have devoured every last lollypop and likely the appeaser himself, just as Hitler could not be satisfied by any concessions short of absolute submission.