Imagine seeing a 15-foot high wave of beer coming right at you. Such a scenario is typically reserved for fiction, but it was a reality for the citizens of St. Giles, London, on October 17, 1814. You might expect thousands of people to help themselves to the free booze on display but in reality, several people drowned in it. The London Beer Flood was a unique event that claimed the lives of at least eight people and here’s how it happened.

Background

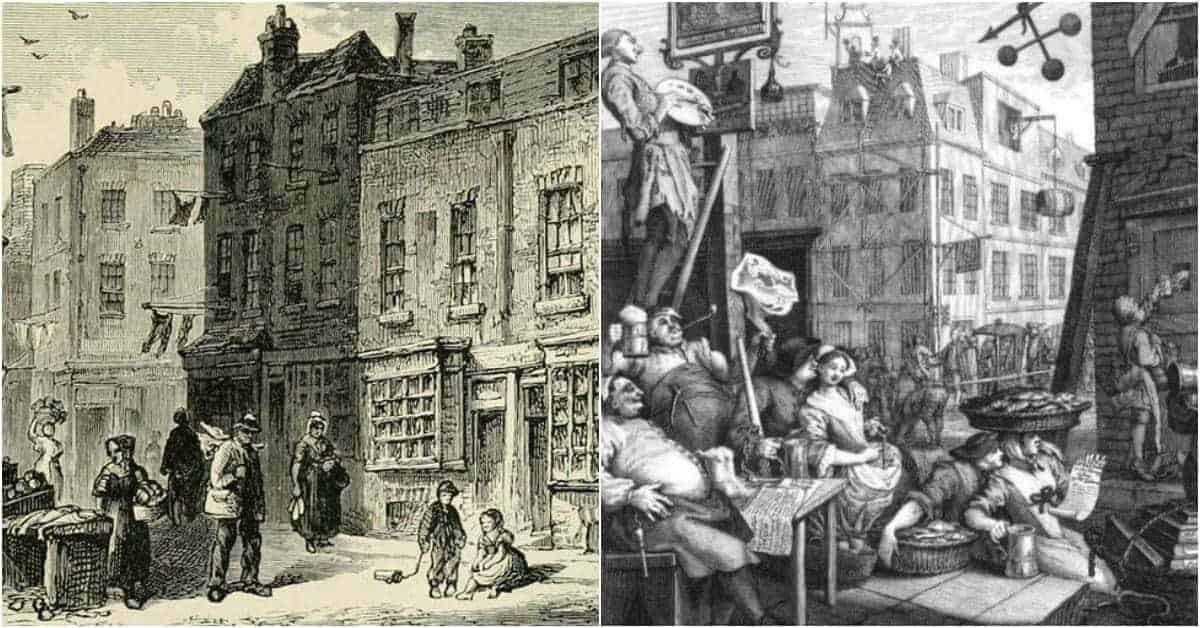

To understand how the London Beer Flood happened in the first place, you need to rewind to half a century before the fiasco. By the second half of the eighteenth century, there was almost a competition amongst London breweries to see who had the largest porter vat. According to Ian S. Hornsey in A History of Beer and Brewing, the brewer with the largest vat received fulsome praise, and the gigantic vats were a remarkable sight.

By 1763, there were vats capable of holding over 1,500 barrels, and by the time of the beer flood, the vats were exponentially larger. For the record, the vat that burst and caused the fiasco could hold approximately 3,550 barrels of beer (the total weight was over 571 tons), but it was a LONG way from being the largest vat in the Meux and Co. Brewery (also known as the Horse Shoe Brewery) where the disaster unfolded.

A contemporary writer, Mrs. Mary Brunton, visited the brewery in 1812 and outlined the enormous size of the vats. The largest cask she saw cost £10,000 at the time and was 70 feet in diameter. It could hold up to 18,000 barrels of beer (£40,000 worth of porter), and the iron hoops around the cask weighed 80 tons by themselves. Brunton also stated that there was a vat that could hold 16,000 barrels. In other words, the London Beer Flood could have been even worse.

Although Meux & Co. claimed the brewery was founded in 1764, there are reports of other brewers in the location before this date. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the brewery was almost in the top 10 in London. The Great Beer Flood was not the first tragedy to happen at the brewery either. In 1794, John Stevenson Junior, the owner of the brewery at the time, fell into a cooler and drowned.

After all sorts of legal wrangling, Henry Meux, and several partners, acquired the Horse Shoe Brewery and its production quickly escalated. From 1809 to 1811, the brewery’s annual production more than doubled from 40,000 barrels to over 103,000. At this point, the Horse Shoe Brewery was #6 in London and Meux merged with a smaller brewery in 1813. The future seemed bright, but then, the brewery was rocked by tragedy.