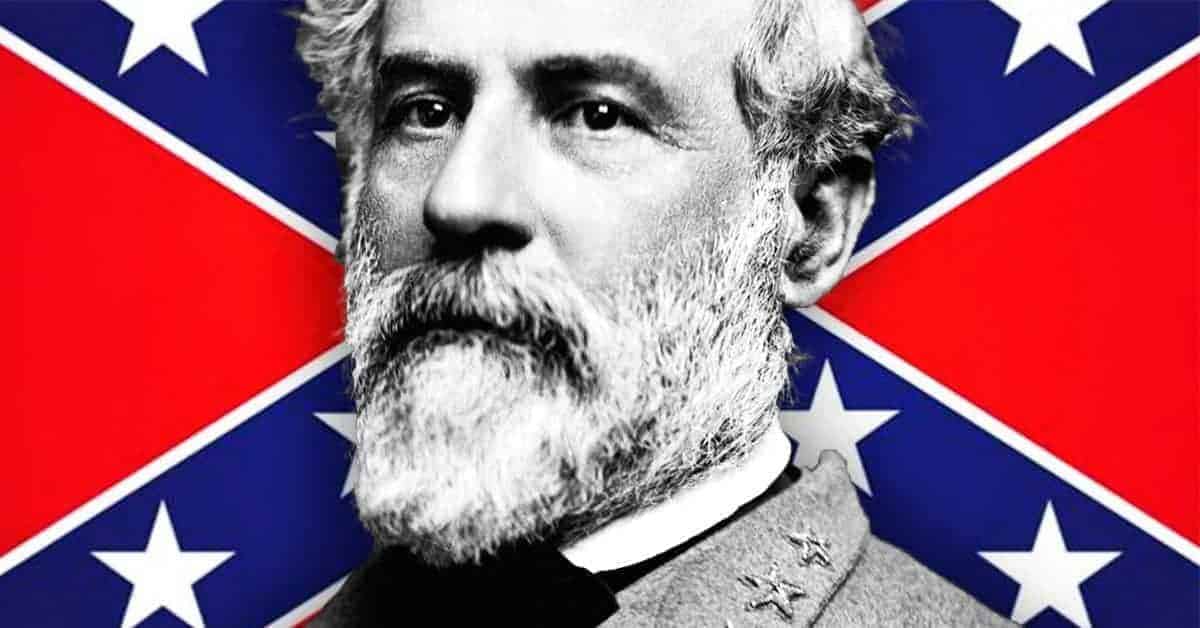

Robert E. Lee has filled the news headlines lately. Lee is a controversial figure due to his service to the pro-slavery Confederacy, viewed as treason by many, and for the heroic status, he maintains to this day. His defenders call him a great soldier while detractors believe him to be a white supremacist. Both of these views are correct. He is remembered as a man with an admirable sense of honor yet he violated his oath to defend the Constitution and vigorously prosecuted a war against his native country.

He denounced secession yet fought to maintain it, leading hundreds of thousands to death or dismemberment. After the war, he announced that he regretted having chosen the military as a career, but his leadership and battlefield tactics are still studied by career officers today, in many nations.

Despite the crushing defeats and severe casualties he inflicted on Union armies, he became a hero in the North in the decades following the Civil War. The US Army named Fort Lee in Virginia for their defeated adversary, the US Navy christened their third ballistic missile submarine USS Robert E. Lee. Hundreds of roads, parks, memorials, monuments, and schools bear his name, and there are statues to his memory all across the country. But in life, Lee supported denying newly emancipated slaves the right to vote, believed that they should be deported from the United States, and believed that freeing the slaves had led to hostility between the races which had previously been absent.

He also supported the institution of free schools for blacks. But as superintendent of Washington College following the war (now Washington and Lee University) he was lax punishing students for racist attacks on blacks and allowed white students to form a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Here are nine facts that are largely forgotten about Robert E. Lee.

He opposed the construction of memorials to the Southern Cause following the war

Lee believed that after the military collapse of the South its only salvation economically and socially was friendly relations with the Northern states and the federal government. After visiting the White House in 1869 at the invitation of President Grant, Lee became a symbol of reconciliation to both North and South.

As the Ku Klux Klan stepped up its harassment and often outright murder of newly freed blacks, many in the South urged a resumption of the war. Lee counseled against it, well aware that the South was weaker than it had been in 1861 when the odds against its success were long. To him a resumption of fighting was unfathomable.

Lee believed that the construction of monuments and memorials to Southern heroes of the war would help foment the push for further insurrection. Further dividing the two sections was bad for the South both economically and psychologically. For Lee, the South’s future lay in the hands of the victorious North, and appeasement rather than opposition was the key to ending reconstruction and what many Southerners believed to be Northern occupation.

Lee believed that appeasement was also the key to harmonious relations with blacks in the South and that monuments to the Confederacy hindered those efforts. But at the same time, Lee argued for the restoration of white political supremacy and the removal of the right to vote for all blacks, regardless of level of education.

From the end of the Civil War until his death Lee supported facing and overcoming (in his mind) the political realities of the day, rather than celebrating the Old South which the Civil War had buried forever.