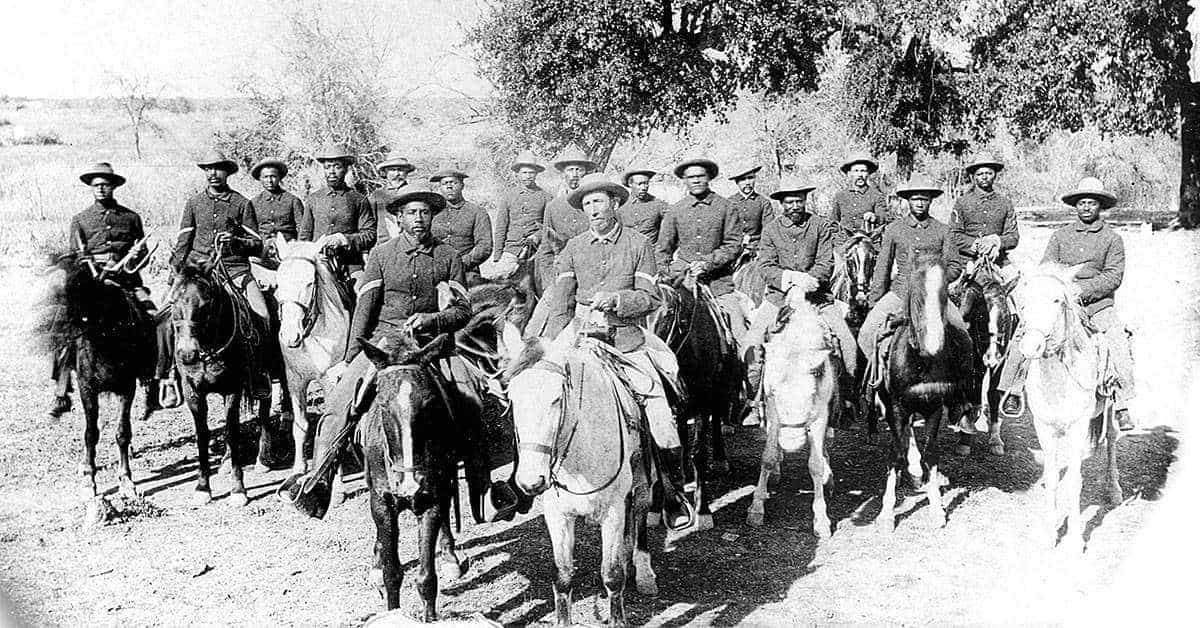

American special operations forces, such as the U.S. Army Rangers, were formally commissioned during the last century. Established in 1952, the United States Special Operations Command officially traces its roots back to the Office of Strategic Services. The true history of American clandestine operations goes back much further than the Second World War, however. A relatively unnoticed group of Black Seminole Scouts, who helped America’s frontier army pacify the Great Plains during the late nineteenth century, has been overlooked for nearly 150 years. These elite scouts were the most effective desert trackers in U.S. Army history and this is their story.

Culture, Conflict, and Relocation

Today’s Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Native American group, consisting of more than 4,000 members and six reservations, spread across the southern region of the state. Including the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, the Florida Seminoles comprise the three officially sanctioned Seminole entities in the United States. They achieved formal recognition in 1957, but their native tribal history extends back much further, to the early eighteenth century. Creek Indians, along with several other Native Southeastern tribes, gradually integrated to form the Seminole Nation, which prospered through the late 1700s into the early 19th century.

The Florida Seminole Nation is historically considered part of the “Five Civilized Tribes,” a broader group consisting of the five Native American cultures first encountered by European settlers during North America’s early colonial period. Along with the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Creeks, the Seminoles were typically regarded as “civilized” by white colonists because they broadly incorporated many European practices within their own respective cultures. The adoption of centralized bureaucracies and converting to Christianity generally facilitated stable relations between these groups over the years. The Seminoles developed a robust trading network in colonial Florida, which economically and geographically flourished over the course of several decades.

Seminole Indians became increasingly independent of their Native American and Euromerican neighbors, rapidly expanding their control over many parts of Florida. Free blacks and escaped slaves frequently sought refuge in the southern lands of the Seminole Nation. Subsequent generations of African-Americans assimilated into Native society but also retained many of their distinct Gullah customs and traditions, which eventually led to the establishment of a unique Black Seminole culture. Tenuous Indian-White relations began to crumble after the Revolutionary War, however, as a nascent U.S. Government began exerting political and territorial pressure on many Native Southeastern groups, sparking the First Seminole War of 1816.

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1819. The Seminoles, meanwhile, surrendered their northern lands and settled in southern Florida. Two subsequent Seminole Wars (1835-42 and 1855-58) marked the costliest period of conflict in the history of the Indian Wars. Seminole warriors frustrated the U.S. Army by employing irregular warfare and guerrilla tactics against a numerically and technologically superior force of well-equipped soldiers. Nevertheless, years of bloody battle eventually exhausted the Seminoles’ limited stores of food and equipment. Tired and hungry, most of the tribe agreed to relocate to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), ostensibly to start a peaceful new life on the frontier.