On the morning of July 2, 1881, a man was having his shoes shined inside the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C. His name was Charles Guiteau, a failed lawyer and amateur theologian from Illinois, and in his pocket sat an ivory-handled revolver.

Guiteau watched the door, waiting for someone important to arrive: the President of the United States, James Garfield. As the President entered the waiting room of the station, Guiteau raised his revolver and fired twice.

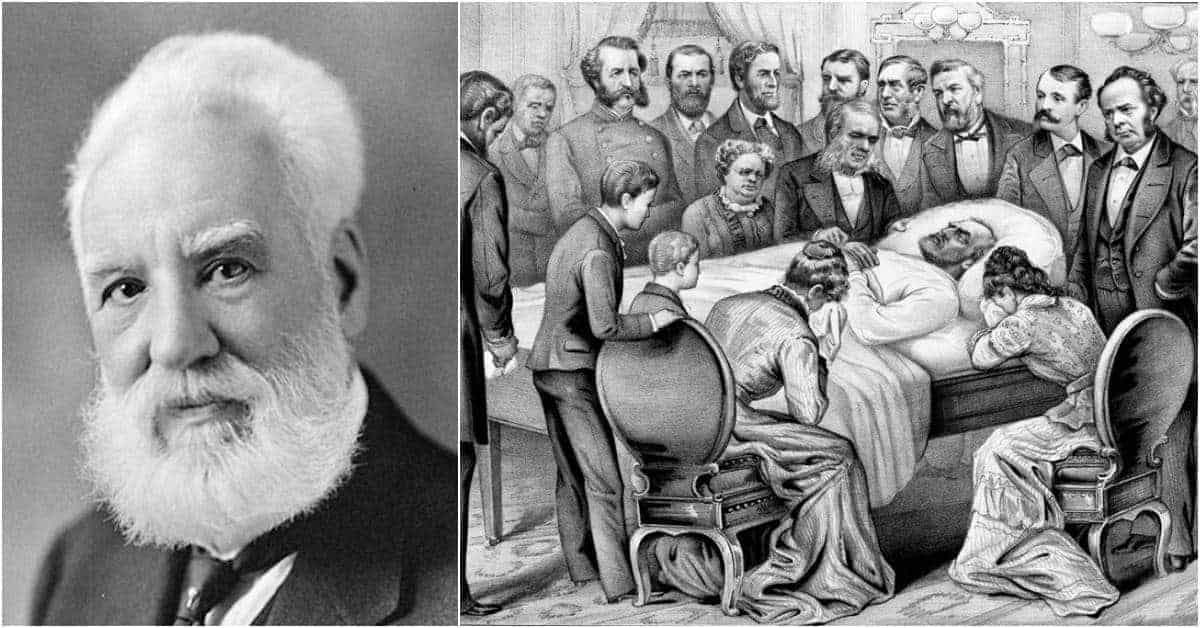

The first bullet grazed Garfield’s shoulder, but the second struck him in the back and lodged in the tissue near his pancreas. As Garfield collapsed, Guiteau slid the gun back into his pocket and began walking quickly towards the exit. However, he didn’t get far.

On the way out, he was stopped by a nearby policeman. Guiteau went quietly into custody. He went so quietly, in fact, that he still had his revolver in his pocket when he arrived at the police station. The arresting officers had forgotten to take his weapon.

Meanwhile, the President was rushed to a waiting carriage and taken back to the White House as the nation tried to make sense of what had just happened.

The assassin offered little explanation of his motives at first. While being arrested, Guiteau cried out, “I am the Stalwart of Stalwarts! Arthur is President now!” The Stalwarts were a faction of the Republican Party opposed to Garfield’s own faction and this statement led many to falsely believe that Stalwart supporters of Vice President Chester A. Arthur were behind the assassination attempt. But while Guiteau seems to have believed that his attack would somehow benefit the Republican party, his true motives were far stranger.

Born in 1841, Guiteau spent most of his life bouncing from one failed endeavor to the next. After failing the entrance exams for the University of Michigan, Guiteau joined a religious commune in Oneida, New York. He seems to have been unpopular with the community, which soon nicknamed him, “Charles Gitout.” He left the commune within a few years and filed a lawsuit against its leader, John Humphrey Noyes. His suit was unsuccessful. Even Guiteau’s father, who had connections with the commune, wrote letters in defense of Noyes. He agreed with Noyes that his son was likely insane or perhaps possessed by Satan.

Guiteau disagreed. In his mind, he was divinely chosen for some great purpose. And after unsuccessfully trying his hand at the law, he turned to theology, writing a book outlining his conception of religion. The work was largely a plagiarized reproduction of the work of John Noyes, and few people paid much attention to it. After traveling from place to place trying to spread his new gospel without any success, Guiteau turned to politics, writing a speech in support of Garfield’s presidential candidacy in the 1880 election. Although almost no one actually heard him give the speech, Guiteau believed that it won Garfield the election. In Guiteau’s mind, that meant the President owed him. And he intended to collect his due.